From :- BBC World News

By :- Nikhil Inamdar (BBC News, London•@Nik_inamdar)

Edited by :- Amal Udawatta

The Trustees of the British Museum

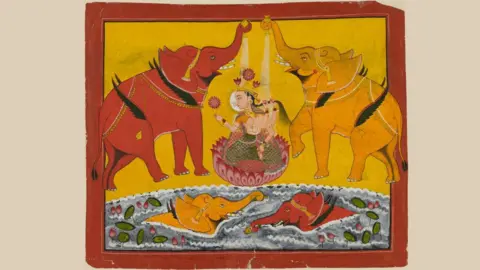

The Trustees of the British MuseumA new exhibition at the British Museum in London showcases the rich journey of India's spiritual art. Titled Ancient India: Living Traditions, it brings together 189 remarkable objects spanning centuries.

Visitors can explore everything from 2,000-year-old sculptures and paintings to intricate narrative panels and manuscripts, revealing the stunning evolution of spiritual expression in India.

Art from the Indian subcontinent underwent a profound transformation between 200BC and AD600. The imagery which depicted gods, goddesses, supreme preachers and enlightened souls of three ancient religions - Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism - was reimagined from symbolic to more recognisably deriving from human form.

While the three religions shared common cultural roots - worshipping ancient nature spirits such as potent serpents or the feisty peafowl - they negotiated dramatic shifts in religious iconography during this pivotal period which continues to have contemporary relevance two millennia apart.

"Today we can't imagine the veneration of Hindu, Jain or Buddhist divine spirits or deities without a human form, can we? Which is what makes this transition so interesting," says Dr Sushma Jansari, the exhibition's curator.

The exhibition explores both the continuity and change in India's sacred art through five sections, starting with the nature spirits, followed by sub-sections dedicated to each of the three religions, and concluding with the spread of the faiths and their art beyond India to other parts of the world like Cambodia and China.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe centrepiece of the Buddhist section of the exhibition – a striking two-sided sandstone panel that shows the evolution of the Buddha - is perhaps the most distinguishable in depicting this great transition.

One side, carved in about AD250, reveals the Buddha in human form with intricate embellishments, while on the other - carved earlier in about 50-1BC - he's represented symbolically through a tree, an empty throne and footprints.

The sculpture - from a sacred shrine in Amaravati (in India's south-east) - was once part of the decorative circular base of a stupa, or a Buddhist monument.

To have this transformation showcased on "one single panel from one single shrine is quite extraordinary", says Dr Jansari.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumIn the Hindu section, another early bronze statue reflects the gradual evolution of sacred visual imagery through the depiction of goddesses.

The figure resembles a yakshi - a powerful primordial nature spirit that can bestow both "abundance and fertility, as well as death and disease" - recognisable through her floral headdress, jewellery and full figure.

But it also incorporates multiple arms holding specific sacred objects which became characteristic of how Hindu female deities were represented in later centuries.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumOn display also are captivating examples of Jain religious art, which largely focus on its 24 enlightened teachers called tirthankaras.

The earliest such representations were found on a mottled pink sandstone dating back about 2,000 years and began to be recognised through the sacred symbol of an endless knot on the teachers' chest.

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Ashmolean Museum, University of OxfordThe sculptures commissioned across these religions were often made in common workshops in the ancient city of Mathura which the curators say explains why there are marked similarities between them.

Unlike other shows on South Asia, the exhibition is unique because it is the "first ever" look at the origins of all three religious artistic traditions together, rather than separately, says Dr Jansari.

In addition, it carefully calls attention to the provenance of every object on display, with brief explanations on the object's journey through various hands, its acquisition by museums and so on.

The show highlights intriguing detail such as the fact that many of the donors of Buddhist art in particular were women. But it fails to answer why the material transformation in the visual language took place.

"That remains a million-dollar question. Scholars are still debating this," says Dr Jansari. "Unless more evidence comes through, we aren't going to know. But the extraordinary flourishing of figurative art tells us that people really took to the idea of imagining the divine as human."

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe show is a multi-sensory experience - with scents, drapes, nature sounds, and vibrant colours designed to evoke the atmospherics of active Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religious shrines.

"There's so much going on in these sacred spaces, and yet there's an innate calm and serenity. I wanted to bring that out," says Dr Jansari, who collaborated with several designers, artists and community partners to put it together.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumPunctuating the displays are screens displaying short films of practising worshipers from each of the religions in Britain. These underscore the point that this isn't just about "ancient art but also living tradition" that's continuously relevant to millions of people in the UK and other parts of the globe, far beyond modern India's borders.

The exhibition draws from the British Museum's South Asian collection with 37 loans from private lenders and national and international museums and libraries in the UK, Europe and India.

Comments

Post a Comment