From - Sky &Telescope

By - Bob King

Edited by - Amal Udawatta

NASA / JPL-Caltech / JAXA

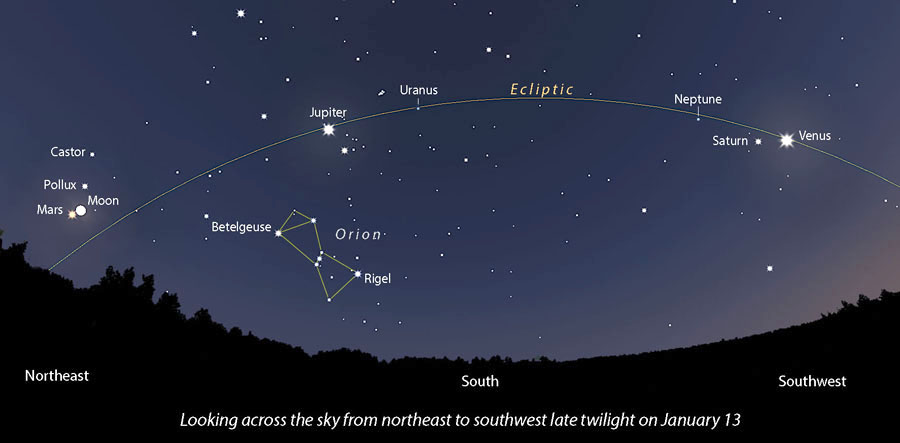

Catch four planets — Venus, Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars — in the evening sky. With good binoculars, Uranus and Neptune also become visible. Plus, Comet ATLAS may survive its close approach to the Sun.

I like easy. Mining the deep-sky or spending a half-hour teasing out Martian surface features have their rewards, but it's been a blast to scan the evening sky this month and enjoy the planets with just my eyes.

Venus and Saturn are paired in the west and will be in conjunction this coming weekend. Turn around and face east, and Jupiter and Mars eagerly greet your gaze. Add in the glitter of the Winter Hexagon and its captive, Betelgeuse, and you've got seven shimmering stars and four bright planets bent on getting your attention the next clear night.

Stellarium, with additions from the author

Maybe you've heard about a rare planetary alignment happening on January 25th. Not to steal the joy, but the four brightest planets have occupied the evening sky simultaneously since early December and will continue to do so through late February — so no need to limit your nights out!

Moreover, it's not rare to have multiple planets in the sky at the same time, though it's a little uncommon for the four brightest to be so well-placed and accessible. The planets can't help but line up, because they all orbit within a few degrees of the solar system plane, better known as the ecliptic. Since Earth occupies the same plane, when we gaze into space, the planets look like bright beads strung across an invisible wire that stretches from horizon to horizon and continues below it to include the morning-sky planets.

In fact, there are actually six of our planetary siblings visible right now at nightfall, although two of them — Uranus and Neptune — require binoculars or a small telescope to spot. To find the ice giants, you can make finder charts at in-the-sky.org: Click the Charts heading. In the drop-down menu select Objects-finder charts. Type the planet's name in the Object box, set the date and click Update.

What's been grabbing attention these evenings is how many planets are visible simultaneously and how tightly bunched they are. Right now, Mercury is in the morning sky and unfortunately hidden in the Sun's glare. It's off the list. But the remaining 6 accessible planets span 136° of sky at the moment.

That's not bad but nowhere close to a record. We saw a tighter gathering of all of the planets back in June and July of 2022, when the full crew plus the Moon spanned 91° of sky before dawn. The cherry on top was that the brightest planets were lined up in order of distance, from Venus (farthest east) to Saturn (farthest west). No such symmetry plays out in the current lineup.

Bob King

Things actually become more interesting in late February. Starting around February 23rd, Mercury begins a bright run in the evening sky. While Saturn will be nearly lost in the glow of dusk, dedicated observers should be able to see both planets during early-to-mid twilight under good conditions with binoculars or a small telescope. They'll be in conjunction, less than 2° apart, on February 25th. As the sky darkens, Neptune, followed by Venus, Uranus, Jupiter, and Mars will appear to make a total of seven planets strung across about 119° of sky.

Stellarium

In case you're wondering if it's possible for all of the planets to align, so they're stacked on top of one another, practically speaking the answer is no. Each planet orbits the Sun with a different inclination, ranging from 0.8° for Uranus to 7° for Mercury. Earth is a special case: Its inclination is 0° because it defines the plane of the solar system. This means the planets, like the Moon, slowly weave above and below the ecliptic plane, precluding a bullseye alignment.

For fun, we can instead calculate how often the eight major planets cluster within 1° of each other. Sky & Telescope Contributing Editor Tony Flanders did the math back in July 2006, and arrived at 13.4 trillion years. But by then, the future Sun will have engulfed Mercury and Venus and messed with the orbits of the surviving planets, preventing such a close alignment from happening.

Comments

Post a Comment