From BBC World News

Edited by Amal Udawatta

Nasa

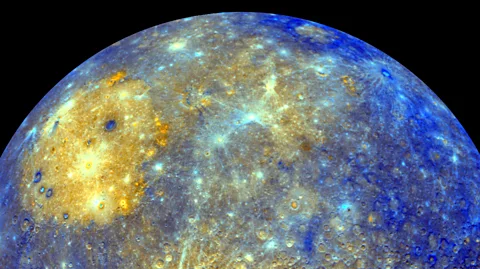

NasaFrom its "absurd" core to the baffling chemical composition of its surface, Mercury is full of surprises – not least the planet's origins. But some answers could be held in rocks found in Cyprus.

Curiosity has killed many an explorer, and Nicola Mari feared he was to be the next.

Driving around Cyprus's remotest mountains, Mari had relied on his cell phone for directions. But as the light of the day faded, so did his phone battery – and he found himself stuck in the middle of nowhere with little idea of the way back to his lodgings. "I'd travelled for more than 50km (31 miles) without seeing another vehicle," he says.

He thought he could remember the way to an inn, where he might refill his stomach, engine, and phone battery – but having arrived there, he found it was deserted. A lucky turn eventually led him to another establishment, but he admits to fearing for his life on those lonely mountain roads. "I made some bad calculations," he says.

Fortunately, his mission was not in vain. Mari is a planetary geologist at the University of Pavia in Italy who studies ways that our neighbours in the solar system formed and evolved. For his PhD, he had studied Martian lava flows. This time, his sights were set on Mercury – by way of Cyprus. His aim was to find a certain kind of rock, named "boninite", that is thought to bear an uncanny similarity to the rocks found on Mercury – a supposition which, if right, could be a clue to the planet's unique origins.

First rock from the sun

Mercury is a planet of extremes. With a total volume little more than the Moon, it is the smallest planet in the Solar System and is situated the closest to the Sun. Mercury has no atmosphere to retain heat, meaning that the temperature on the surface varies from 400C during the day to -170C (750F to -275F) at night. It also has the shortest orbit of any planet in the Solar System; each year lasts just 88 Earth-days.

Mercury's location has made it very difficult for scientists to study. One reason is the heat. Spacecraft approaching the planet need to be able to withstand scorching temperatures as they wander so close to the Sun. The other is gravity. The nearer you get to the Sun, the stronger its pull, accelerating the speed of the spacecraft. This makes delicate manoeuvres much harder to pull off. To avoid it travelling too fast, the spacecraft can take a convoluted route, with lots of detours around other planets, which helps to slow its path – but the spacecraft still need a lot of fuel to decelerate and gain control of its movements.

Nicola Mari

Nicola Mari"From the trajectory point of view, it's probably harder to reach than Jupiter," says Ignacio Clerigo, spacecraft operations manager of BepiColombo, the European Space Agency's ongoing mission to Mercury, a project Mari's work is contributing to.

These difficulties mean that Mercury has been less well-studied than our other neighbours. Two previous missions – Mariner 10 and Messenger – had flown close enough to map its surface, which is pockmarked with craters – and revealed some major surprises about its structure.

One surprise was the planet's core. The other rock-based planets – Venus, Earth and Mars – all have a relatively tiny core, surrounded by a thick mantle made of magma, and a hard crust. Mercury's crust, however, appears to be surprisingly thin, while its core is unexpectedly huge compared to the mantle. "It's absurd," says Mari.

Even more unexpectedly, these missions revealed that Mercury is surrounded by a magnetic field. This, combined with its density, suggests that it has an iron core – and, like that of the Earth, the core may be partly molten.

To add to the mystery, the ratio of chemicals on Mercury's surface is highly unusual. By using a technique known as "spectrometry" to analyse the chemical composition of the planet at a distance, scientists know that Mercury has a much high concentration of thorium than its nearest neighbours. Thorium should have evaporated in the extreme heat of the early Solar System. Instead, its thorium content is closer to that of Mars – three planets away – which would have formed at cooler temperatures due to its distance from the Sun.

Nicola Mari

Nicola MariSuch anomalies have led some planetary scientists to hypothesise that Mercury originally formed at a more distant point from the Sun, near to Mars – and that it started out with a much bigger mass, around the size of the Earth, that would befit its large core. At some point in its history, however, it is hypothesised that Mercury collided with another planetary body that sent it spinning towards the Sun. Such a collision could have blown away its crust and much of its mantle but left behind the huge liquid core.

"The Mercury we see today may be nothing more than the kernel of the planet that was once there," says Mari.

Alien rocks

The ideal way of investigating this theory would be to analyse samples of rocks from the crust of Mercury, or to drill into its mantle – but no probe has been able to land on the surface, leading scientists on Earth to look for other sources of information.

Some clues may come from a class of meteorites known as aubrites, which are named after the French commune of Aubres where they were first discovered. These rocks have a similar chemical composition to Mercury, and some scientists have even hypothesised that they may be debris from the interplanetary collision that knocked Mercury into its current position.

It is a tempting idea, but Mari is sceptical. The evidence so far, he says, suggests the aubrites come from asteroids that formed in the same part of the solar nebula as Mercury – but were never part of the planet itself.

Comments

Post a Comment