From - Independent Magazine

By - David Keys

Edited by - Amal Udawatta

New research has pinpointed the likely time in prehistory when humans first began to speak.

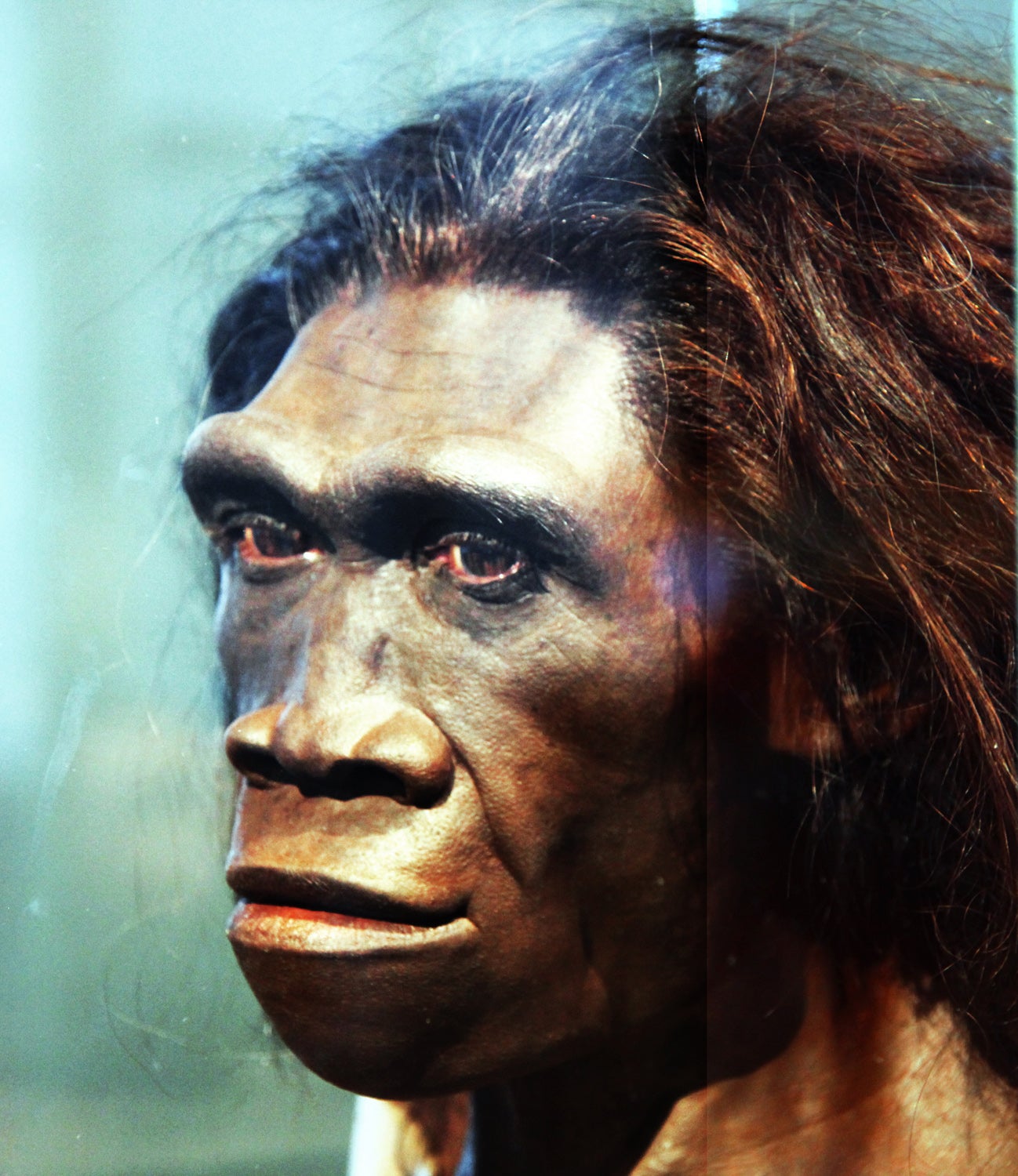

Analysis by British archaeologist Steven Mithen suggests that early humans first developed rudimentary language around 1.6 million years ago – somewhere in eastern or southern Africa.

“Humanity’s development of the ability to speak was without doubt the key which made much of subsequent human physical and cultural evolution possible. That’s why dating the emergence of the earliest forms of language is so important,” said Dr Mithen, professor of early prehistory at the University of Reading.

Until recently, most human evolution experts thought that humans only started speaking around 200,000 years ago. Professor Mithen’s new research, published this month, suggests that rudimentary human language is at least eight times older. His analysis is based on a detailed study of all the available archaeological, paleo-anatomical, genetic, neurological and linguistic evidence.

When combined, all the evidence suggests that the birth of language occurred as part of a suite of human evolution and other developments between two and 1.5 million years ago.

Significantly, human brain size increased particularly rapidly from 2 million BC, especially after 1.5 million BC. Associated with that brain size increase was a reorganisation of the internal structure of the brain – including the first appearance of the area of the frontal lobe, specifically associated with language production and language comprehension. Known to scientists as Broca’s area, it seems to have evolved out of earlier structures responsible for early humanity’s ability to communicate with hand and arm gestures.

New scientific research suggests that the appearance of Broca’s area was also linked to improvements in working memory – a factor crucial to sentence formation. But other evolutionary developments were also crucial for the birth of rudimentary language. The emergence, around 1.8 million years ago, of a more advanced form of bipedalism, together with changes in the shape of the human skull, almost certainly began the process of changing the shape and positioning of the vocal tract, thus making speech possible.

Other key evidence pointing to around 1.6 million BC as the approximate date humans started speaking, comes from the archaeological record. Compared to many other animals, humans were not particularly strong. To survive and prosper, they needed to compensate for that relative physical weakness.

In evolutionary terms, language was almost certainly part of that physical strength compensation strategy. In order to hunt large animals (or, when scavenging, to repel physically strong animal rivals), early humans needed greater group planning and coordination abilities – the development of language would have been crucial in facilitating that. Significantly, date-wise, human hunting began around two million years ago – but seems to have substantially accelerated by around 1.5 million years ago. Around 1.6 million BC also saw the birth and inter-generational cultural transmission of much more sophisticated stone tool technology. That long-term transfer of complex knowledge and skills from generation to generation also strongly implies the existence of speech.

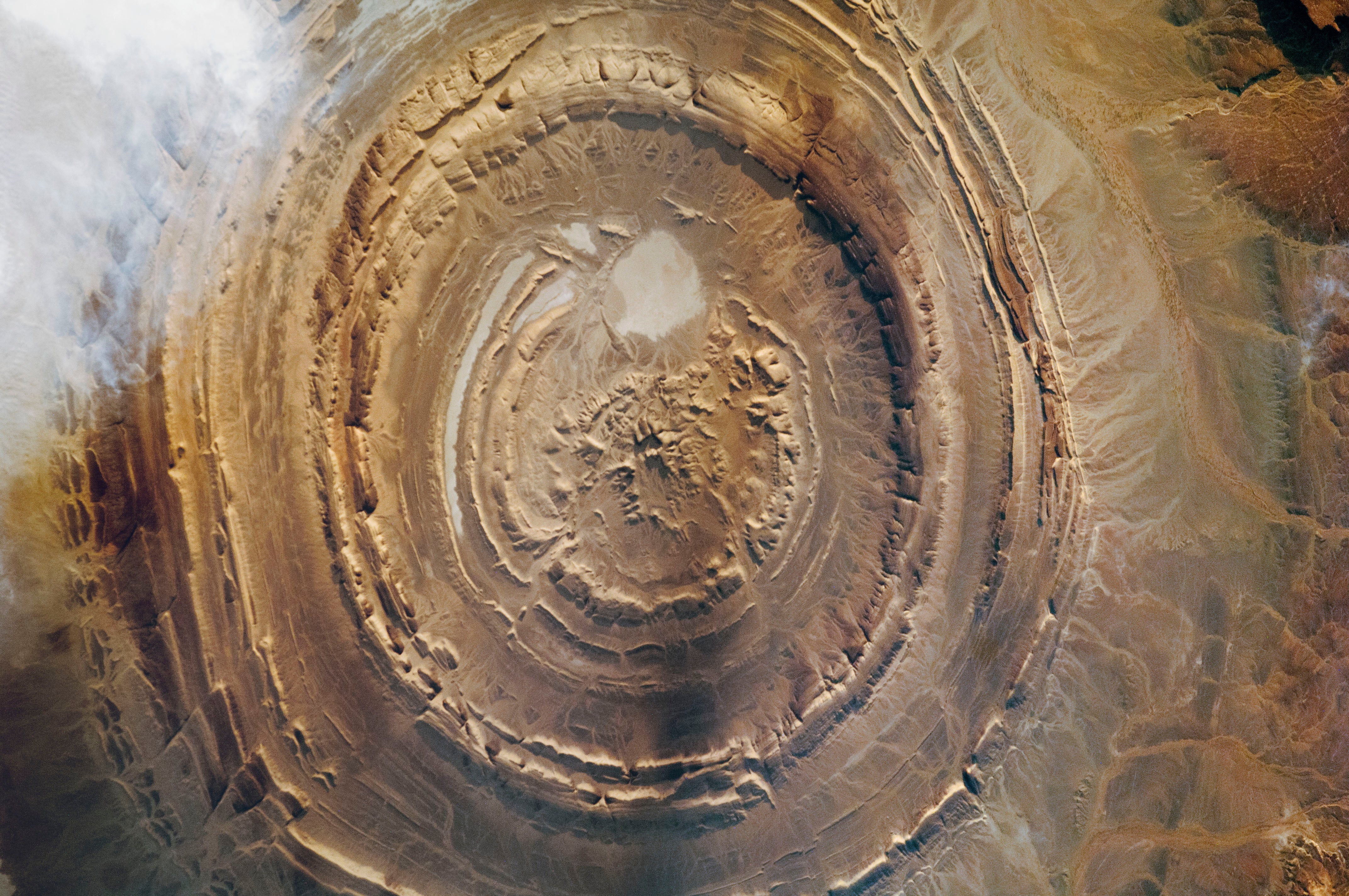

What’s more, linguistic communication was probably crucial in allowing humans to survive in different ecological and climatic zones – it’s probably no coincidence that humans were able to massively accelerate their colonisation of the world around 1.4 million years ago, ie, shortly after the likely date of the birth of language. Language enabled humans to do three key forward-looking things – to conceive of and plan future actions and to pass on knowledge.

“That’s how language changed the human story so profoundly,” said Professor Mithen. His new research, outlined in a new book, The Language Puzzle, published this month, suggests that before around 1.6 million years ago, humans had had a much more limited communication ability – probably just a few dozen different noises and arm gestures which could only be deployed in specific contexts and could not, therefore, be used for forward-planning. For planning, basic grammar and individual words were needed.

Professor Mithen’s research also suggests that there appears to be some continuity between very early human languages and modern ones. He believes that, remarkably, some aspects of that first linguistic development 1.6 million years ago still survive in modern languages today. He is proposing that words, which – through their sounds or length – describe the objects they stand for, were almost certainly among the first words uttered by early humans.

Comments

Post a Comment