Scientists have picked up shock waves from the orbit of supermassive black holes at the heart of distant galaxies as they begin to merge.

This may be the first direct evidence of giant black holes distorting space and time as they spiral in on each other.

The theory is that this is how galaxies grow. Now astronomers may soon be able to watch it happen.

One of the groups that made the discovery is the European Pulsar Timing Array Consortium (EPTA), led by Prof Michael Kramer of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn.

He told BBC News that the discovery had the potential to change astronomers' ideas about the cosmos forever.

"It could tell us if Einstein's theory of gravity is wrong; it may tell us about what dark matter and dark energy, the mysterious stuff that makes up the bulk of the Universe, really is; and it could give us a new window into new theories of physic

Further study might give new insights into the role supermassive black holes play in the evolution of all galaxies.

Dr Rebecca Bowler, of Manchester University, told BBC News that researchers believe there to be gigantic black holes at the heart of all galaxies and that that they grow over billions of years. But so far that has all been theoretical.

"We know supermassive black holes are there, we just don't know how they got there. One possibility is that smaller black holes merge, but there has been little observational evidence for this.

"But with these new observations we could see such a merger for the first time. And that directly will tell us how the most massive black holes form," she said.

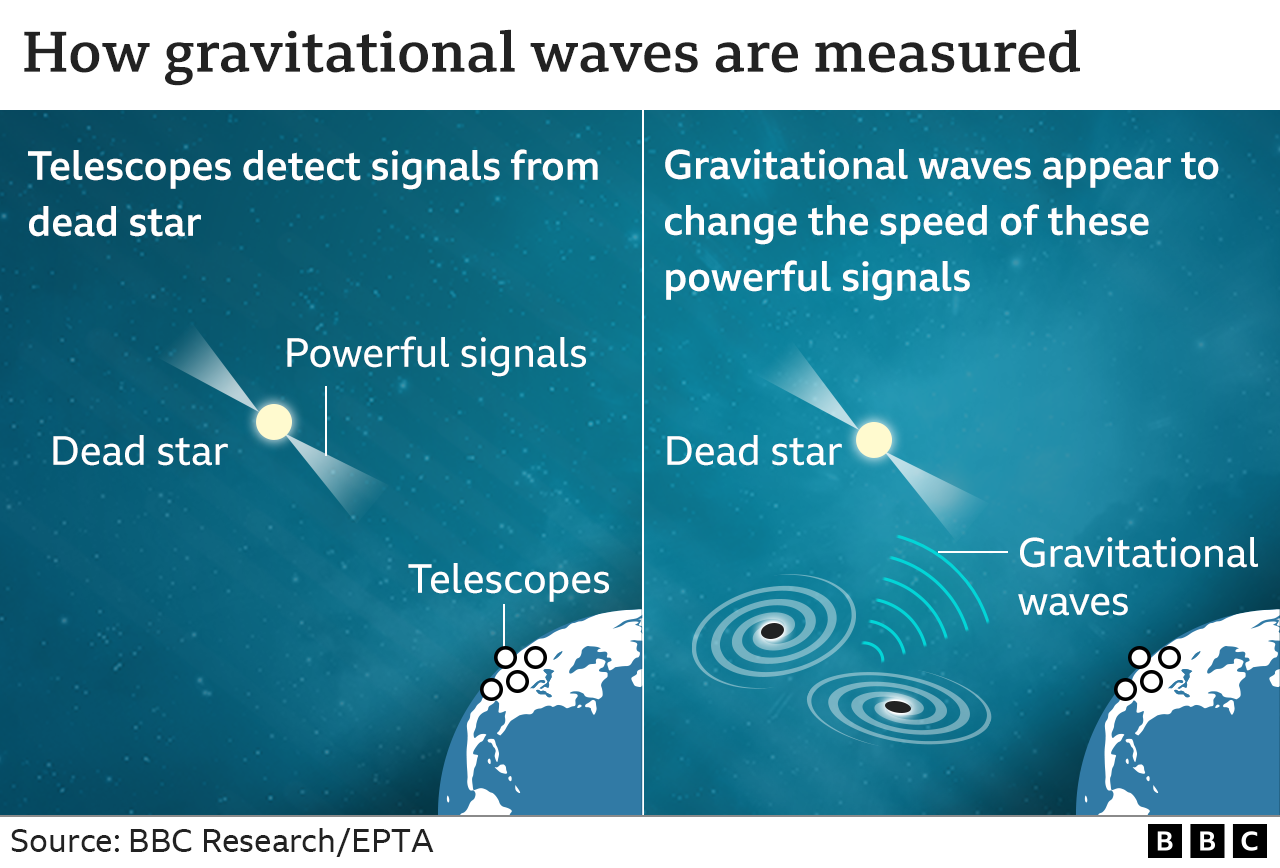

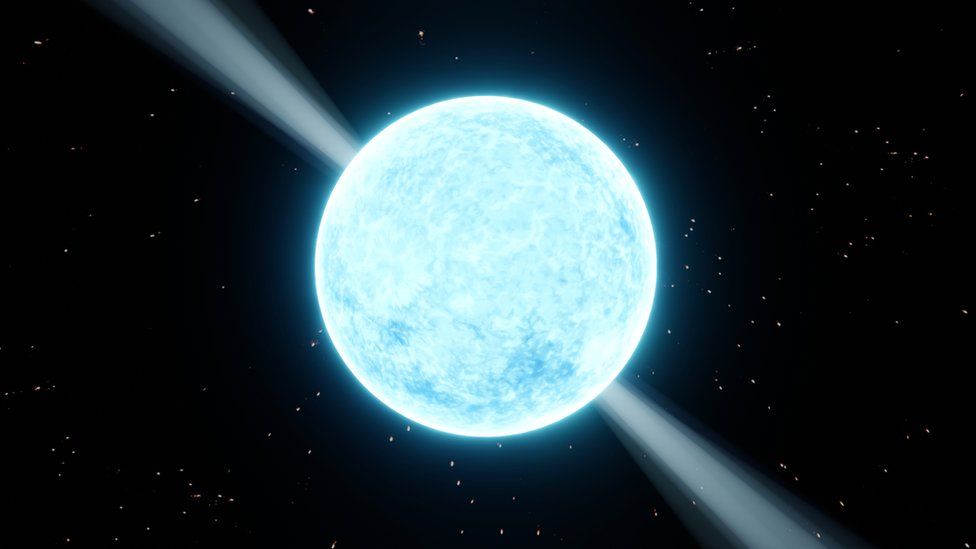

The observations were made by studying signals from dead stars called pulsars. These rotate and send out bursts of radio signals at extremely precise intervals.

But researchers, which include astronomers from the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank in Cheshire and from Birmingham University, have found that these signals are reaching Earth ever so slightly faster or slower than they should be. And they say the time distortion is consistent with gravitational waves created by the merger of supermassive black holes across the Universe.

Dr Stanislav Babak from Laboratory APC at CNRS, France, said gravitational waves carried information about ''some of the best-kept secrets of the Universe".

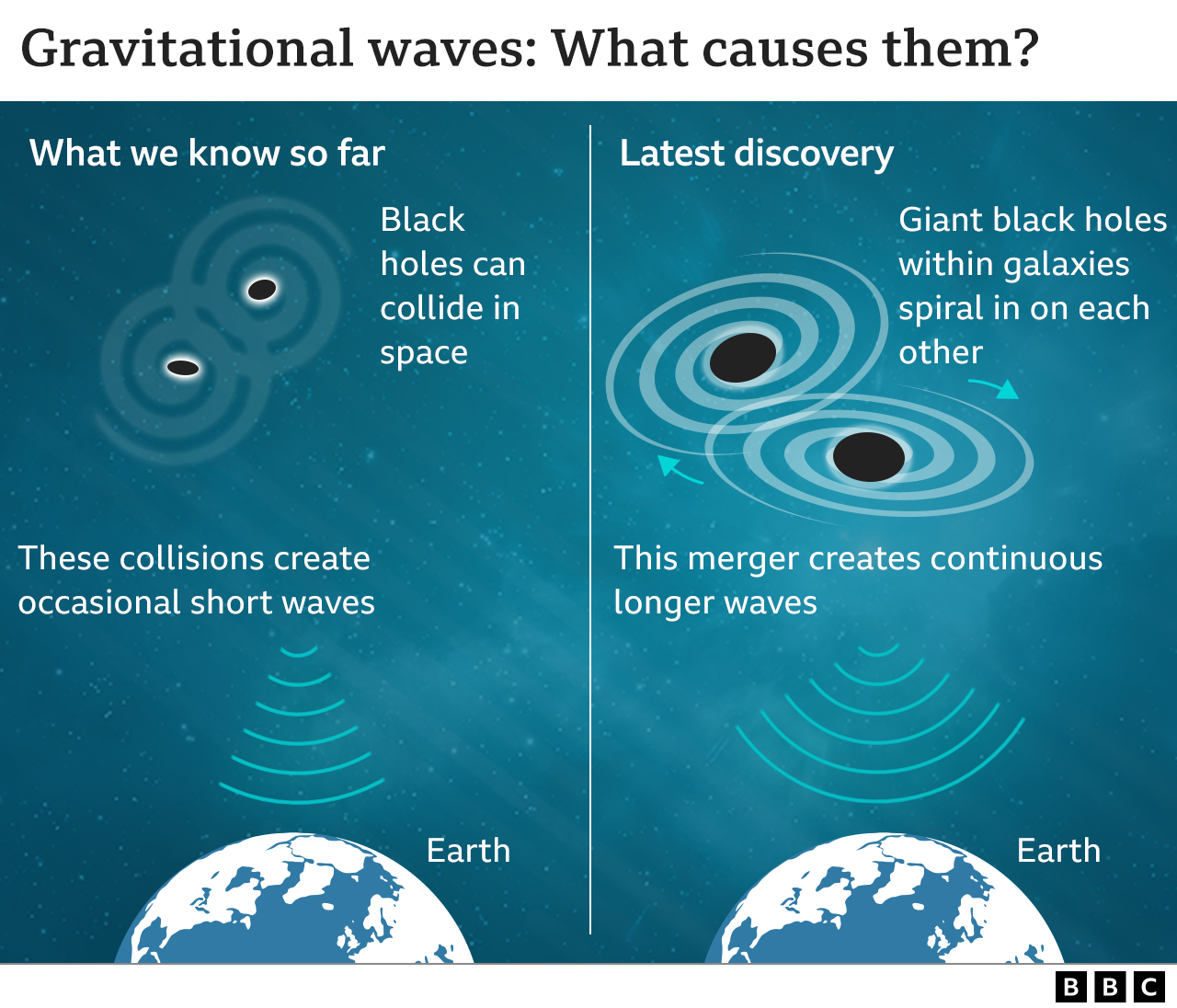

The newly found gravitational waves are different to the ones detected to date. Those earlier waves are caused by much smaller, star-sized black holes crashing into each other.

The type described in the latest research are thought to be from black holes that are hundreds of millions of times more massive, spiralling in on each other as they get ever closer.

Their gravitational upheaval is so powerful that it distorts time and space - a process that can continue for billions of years until the supermassive black holes finally merge.

The gravitational waves scientists have discovered previously can be thought of as brief rumbles, whereas the new ones are akin to a background hum that is around us all the time.

Their next step is to take more readings and combine observations. As further progress is made, another goal is to be able to uncover individual pairs of supermassive black holes - assuming they are the source.

It's possible the gravitational waves could also be caused by other exciting phenomena, such as the very first black holes ever created, or exotic structures called cosmic strings, both of which can be thought of as seeds from which the Universe grew.

What are gravitational waves?

Gravity is a constant force in our everyday lives. If you let go of a cup it falls and smashes on the ground each time you do so. But in space gravity does not stay the same. It can change if there is a sudden and catastrophic event - such as the collision of black holes.

The event is so cataclysmic that space and time itself is distorted and ripples are sent across the Universe - as happens when a pebble is dropped in a pond.

In the case of gravitational waves, everything in the Universe - the stars, planets and even us - are the water. Everything gets squeezed and stretched and then squashed and flattened ever so slightly as the ripples pass over us. And just like in a pond, the ripples quickly get smaller and disappear.

Gravitational waves from the merger of star-sized black holes were directly detected for the first time in 2015. Very sensitive laser systems measured the ripples produced in the end moments before the collision.

For the type of waves coming from the spiralling supermassive black holes, the pulsar approach is picking up the ripples produced in the billions of years before the final union.

This is akin to a continuous stream of pebbles being thrown into the pond. And because the mergers are happening all across space, the signal comes across as a cacophony.

The EPTA has combined results with a consortium in India (InPTA) and published their study results in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Three other separate, competing research groups, from North America (NANOGrav), Australia (PPTA) and China (CPTA), have published similar assessments, sparking huge excitement across the physics and astronomy community.

Scientists must first confirm their observations. None of the research groups have data that passes the gold standard of less than one in a million chance of error, which is generally required for conclusive proof - although combined, the various teams' results are certainly compelling.

Comments

Post a Comment