From - Sky & Telescope,

By - Monica Young,

Edited by - Amal Udawatta,

NASA / ESA / CSA / Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

ANOTHER BLOW FOR ATMOSPHERES IN THE TRAPPIST-1 SYSTEM

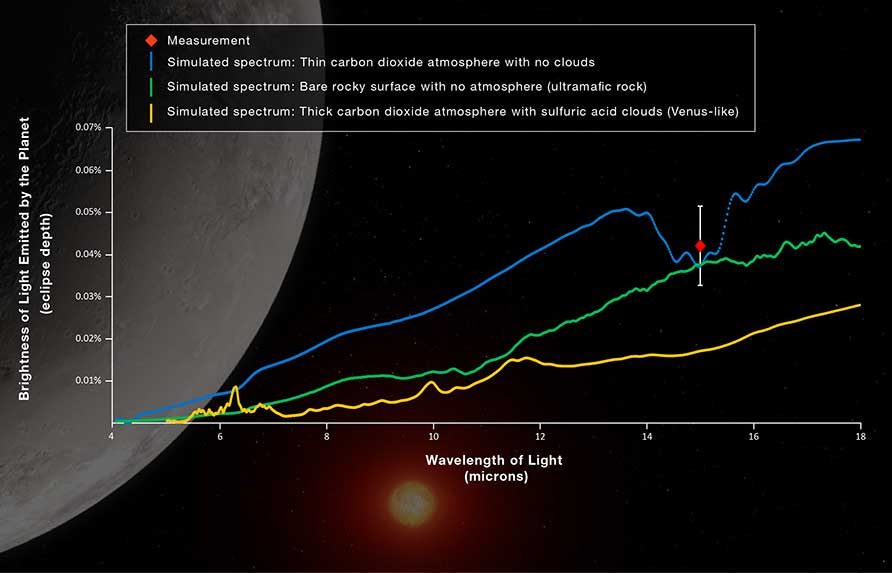

Astronomers are using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to take on the seven planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system, one by one. Observations have already showed the innermost world, TRAPPIST-1b, is airless. Now, new data suggest TRAPPIST-1c could at best host a thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, and it's still possible that c is just as bare as b.

The team, led by Sebastian Zieba (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Germany), watched TRAPPIST-1c pass behind its star using JWST's mid-infrared camera, capturing its dayside brightness at 15 microns — a wavelength that carbon dioxide molecules absorb.

NASA / ESA / CSA / Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

All seven of the TRAPPIST planets are Earth-size worlds, and they're good targets for JWST because the system is only 40 light-years away. However, the planets orbit a red dwarf star — one that's prone to emitting high-energy radiation now, and it was even more active in its youth. Since their discovery, astronomers cautioned that the planets might have had their atmospheres stripped away long ago. Upcoming observations will probe the viability of atmospheres on the system's outer worlds.

Read more about these results in Nature and in JWST's press release.

JUPITER'S YOUNGER SIBLING

Kyle Franson ( University of Texas at Austin) / W. M. Keck Observatory

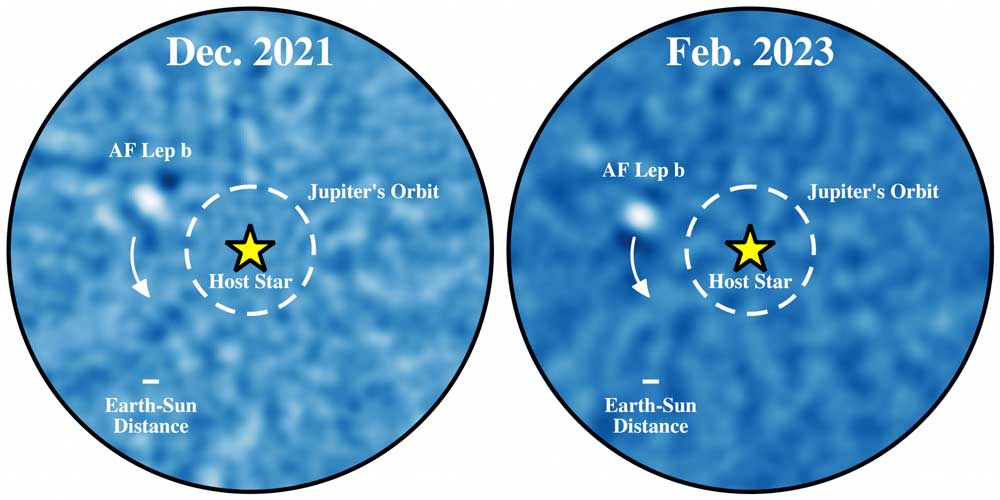

We can directly image exoplanets, but so far our ability to do so has been limited to young, massive, and far-out worlds. Now, astronomers have directly imaged one of the lowest-mass planets to date.

Named AF Leporis b, the planet is three times Jupiter’s mass and, at 8 astronomical units (8 a.u.), only a bit farther from its star than Jupiter is to the Sun. Jupiter’s “younger sibling” is circling a Sun-like star 87.5 light-years away.

Planets amenable to imaging carry three main qualities: Young planets still emit an infrared glow powered by the heat of their formation, and the more mass a planet has the more it will glow. Plus, the farther away it is from its brilliant host star, the easier it is to separate out its light using the technique of coronography. Advances in those techniques have enabled astronomers to pick out planets closer to their stars.

Kyle Franson and Brendan Bowler (both at University of Texas at Austin) took a closer look at stars likely to host planets, based on the way those stars “wiggled” on the sky over 25 years of observations from the Hipparcos and Gaia satellites. Then they used used the Keck II Telescope’s Near-Infrared Camera 2 Vector Vortex Coronagraph to capture the world. The team plans to follow up with JWST observations in order to characterize the giant's atmosphere.

Comments

Post a Comment