From Sky&Telescope

By - Jan Hattenbach,

Edited by Amal Udawatta,

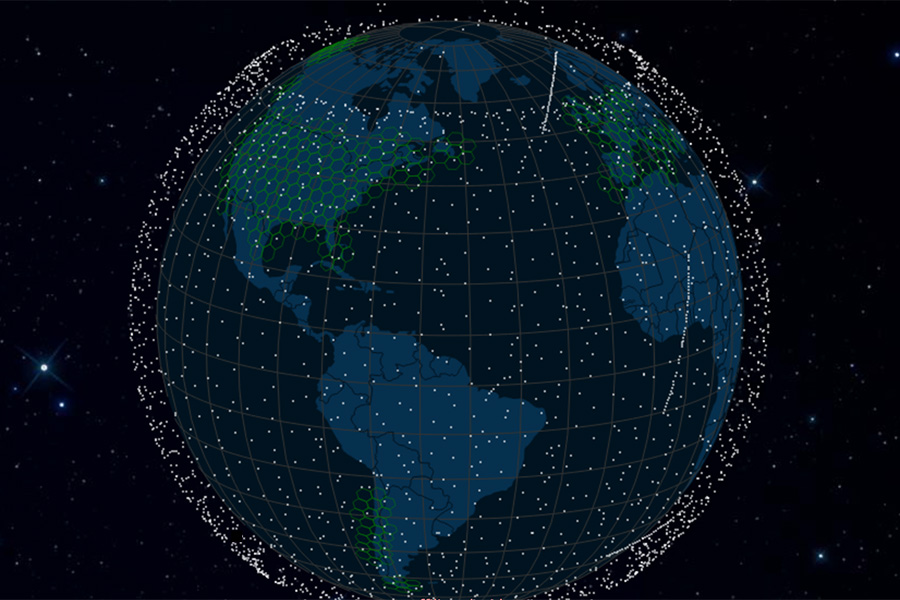

satellitemap.space

Astronomers are sounding the alarm about low-Earth orbit satellites and space debris as significant contributors to light pollution that will affect even the remotest earthbound stargazer.

Anyone who has watched the night sky recently knows it: Satellites are everywhere. They flash across the firmament, paint streaks on photos, and irritate stargazers. In just three years since the advent of so-called megaconstellations, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, light pollution by objects in Earth’s orbit has moved from non-topic to possibly the most serious threat to ground-based astronomy. And, as John Barentine (Dark Sky Consulting) and his colleagues discuss in a paper published in Nature Astronomy, it could get worse — much worse.

“We fear that faint astrophysical signals will become increasingly lost in the noise due to satellite megaconstellations,” the team writes. The hunt for potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) is one possible victim of orbital overkill: “Hazardous near-Earth objects that sky surveys may fail to detect often first appear in our skies in the twilight hours around sunset and sunrise, times when satellites and space debris are most likely to interfere with observations.”

As if to prove their point, a Japanese lunar probe named EQUULEUS fooled NEA-hunters just last week, causing astronomers to waste time on follow-up observations before they figured out what they were looking at.

NO ESCAPE

Satellites don’t shine on their own. They reflect sunlight as they circle our planet. Depending on size, design, orbital height, and solar depression (how low the Sun sinks below the horizon), they may be more or less bright, appearing as moving “stars” to an observer on the ground. Some of them rival the brightest stars, but even the ones invisible to the unaided eye cause streaks on astronomical images. In summer season, they bother high-latitude observers all night; during winter and closer to the equator, satellites are more visible toward dusk and dawn.

Since 2019, the number of functional satellites in low-Earth orbit has more than doubled. But the real problem lies in the near future: Plans to launch up to 100,000 more within just a few years are well underway.

Satellites are more than just annoying moving dots. In 2021, Miroslav Kocifaj (Slovak Academy of Sciences) and colleagues estimate in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society that the accumulated light reflected by all large and small space objects has already made the night sky at zenith up to 10% brighter than it was at the beginning of the Space Age. This is true world-wide, even in remote places where ground-based light pollution is absent. There is no escape from space-based light pollution.

Given this projection, Barentine’s team expects that by 2030 the night sky at zenith will be at least 12% brighter as compared to a natural dark sky, counting the effects of both intact satellites and debris. And in fact, debris have the most impact. “Recent work confirmed that intact satellites will only add about 1% to the diffuse brightness of the zenith,” Barentine adds.

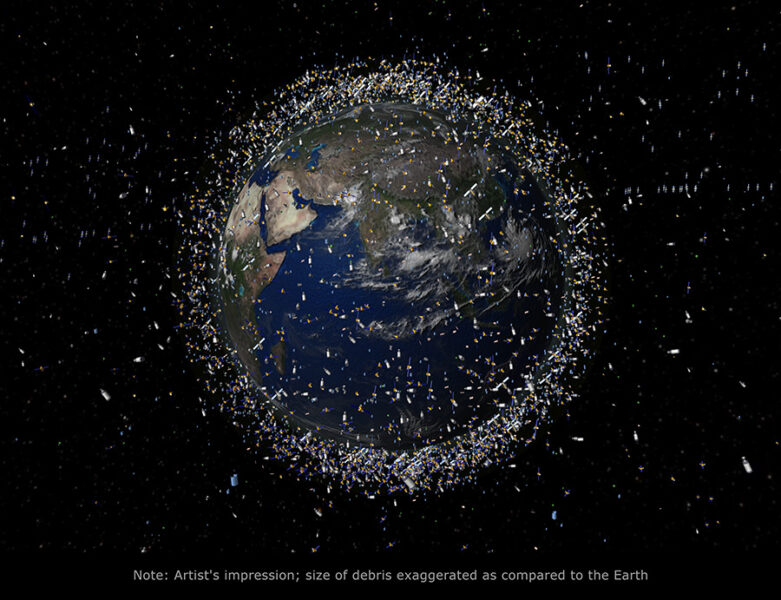

IT’S THE DEBRIS

ESA

In the January 2022 Astronomy & Astrophysics, Cees Bassa (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy) and others argued that small debris fragments are having the greatest effect on sky brightness: "The macroscopic satellites composing the constellations . . . will not contribute much to the diffuse sky brightness provided they are not ground into microscopic debris.” Space debris, however, has the potential to seriously brighten our night sky globally for decades and even centuries to come.

Space debris is anything human-made in orbit that isn’t a working piece of technology: retired or broken satellites, leftover rocket stages, satellite parts and tiny pieces from collisions. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that, as of December 2022, some 36,500 objects larger than 10 cm orbit Earth. Smaller objects are harder to track, and their number more difficult to estimate. ESA believes that there could be up to 1 million pieces large enough to seriously damage working satellites in orbit, and 130 million smaller ones down to 1 mm.

So far, space-debris has mostly been a concern for satellite operators, as even cm-size particles in orbit can carry enough kinetic energy to damage or destroy satellites. But these fragments, too, reflect sunlight, albeit only a tiny amount each, so their accumulated light increases the overall brightness of the night sky.

By how much depends on how frequently the many, many satellites to be launched will collide with each other. Such catastrophic events, whether accidental or intentional, create huge clouds of debris, which can in turn cause more collisions.

In a densely populated environment, with hundreds of thousands of satellites of competing enterprises sharing similar orbital altitudes, any one collision could lead to a cascade effect that will not only render certain orbits useless for satellite operation, but will also change our night skies for generations to come. In the latter calculation, even small debris may have a significant impact due to their sheer number.

If too many debris-generating events occur, Bortle 1 skies — already rare on our planet — could be practically impossible to find except in deep winter nights at very remote locations. For professional astronomy, Barentine’s team concludes, losing darkness even at remote sites translates to higher cost to achieve certain scientific goals. As night sky brightness rises, they write, the exposure time required to reach any particular signal-to-noise ratio increases concomitantly.

THE SOLUTION: FEWER SATELLITES

So far, some companies have attempted to reduce the reflectivity of their satellites, and astronomers have worked on algorithms to remove satellite streaks from their data. But these strategies, Barentine’s team writes, have had only limited effect. For example, SpaceX’s “DarkSat” and “VisorSat” designs failed to reduce Starlink brightness below naked-eye visibility, and both designs were ultimately abandoned for engineering reasons. Correction methods may help clean up astronomical images but will not be able to recover all the data. Most importantly, none of these strategies remedy the debris problem.

“Perhaps the mitigation option least palatable to the commercial space industry, but one that governments may certainly impose, is to simply launch fewer satellites into near-Earth space,” the researchers conclude. In the end, they write, restrictions of objects allowed at certain altitudes may be the only way forward for sustainable space.

Comments

Post a Comment