From - Sky & Telescope,

By - Bob King

Edited by -Amal Udawatta,

Bob King

Time-telling goes way back. Early humans watched the daily and nightly perambulations of the Sun and Moon to mark the passage of time. Even the shadow of a stick jabbed into the ground could serve as a primitive clock. The earliest manufactured timekeeping devices were sundials and water clocks. In a water clock, water dripped through a hole in the bottom of one container into another. Tower clocks that marked the hour by sounding bells appeared in the late 13th century. Clocks with familiar faces and hands made their appearance in the 1700s.

Three hundred years later, cell phones and digital clocks help us keep track of the time. Cell phones get their time directly from Global Positioning (GPS) satellites or through the nearest cell tower, which also uses GPS. Each of the current 31 GPS satellites (at least 24 are operational at any time) houses multiple atomic clocks that determine the time to within 100 billionths of a second.

Paulsava / CC BY-SA 4.0

Atomic clocks measure the length of a second — the basic unit of all modern timekeeping — is the time that elapses during 9,192,631,770 transitions from a lower to a higher energy state of the isotope cesium-133 when stimulated by microwave radiation. Far removed from our everyday experience of time, the “vibrations” are so precise, atomic clocks are accurate to 1 second in about 100 million years.

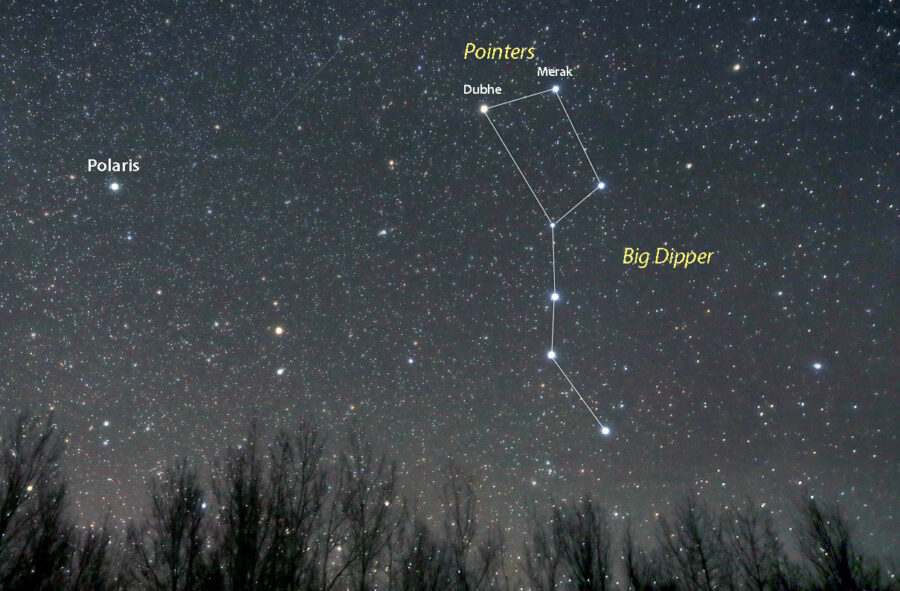

Although considerably less precise, the ancient way of telling time by the stars will still get you by in a pinch. I like to take a walk most nights, turning left at the end of my driveway and ambling north. When it’s clear, I always see the Big Dipper. In spring, those seven bright stars wheel nearly overhead; in fall they skirt the treetops. The two stars at the end of the bucket, Dubhe and Merak, make up an asterism called the Pointers. Shoot an imaginary arrow through them, and it will point you to Polaris, the North Star.

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

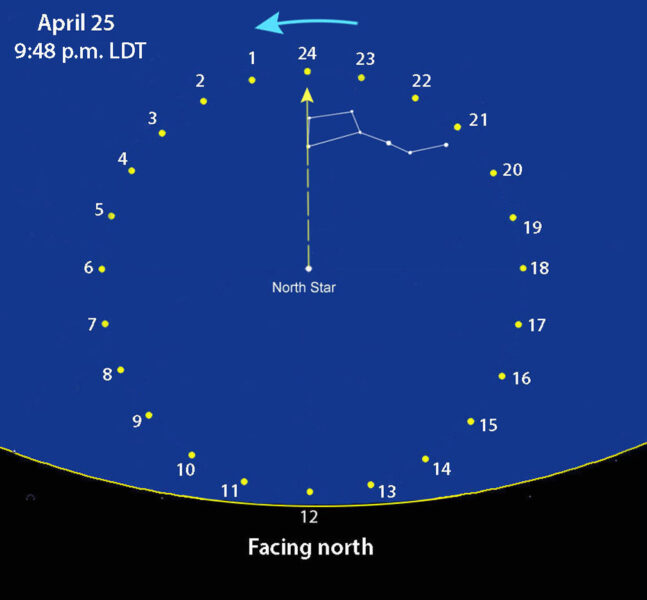

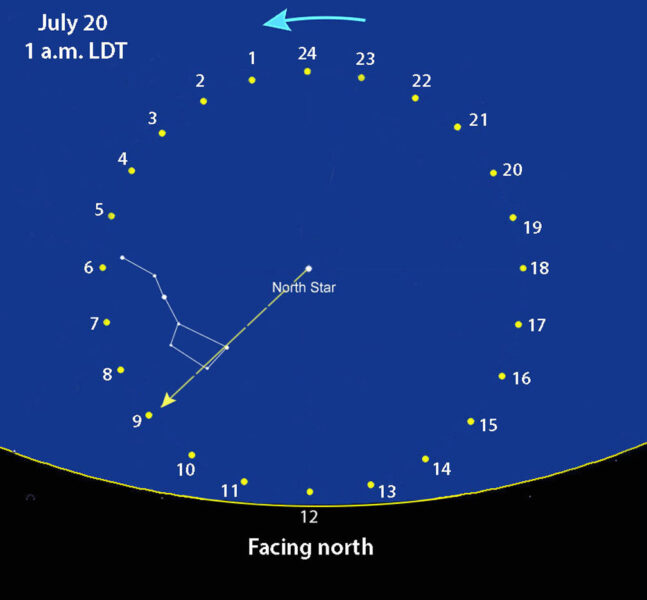

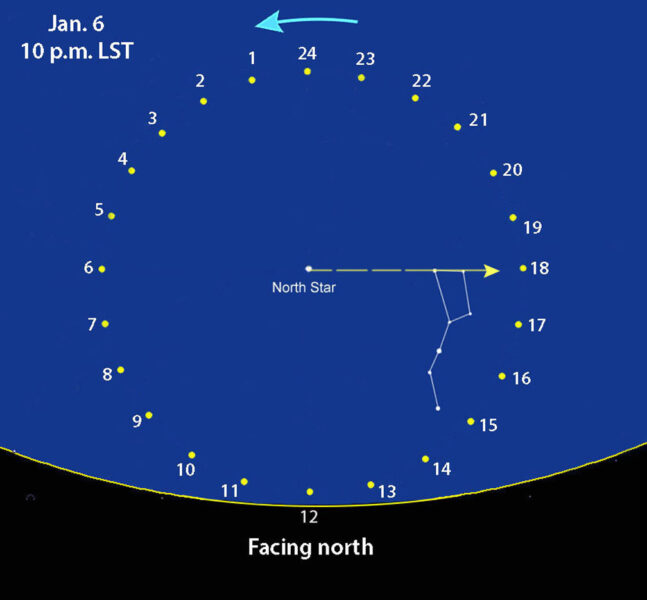

To make our stellar timepiece, we start at Polaris and treat it as the center of a classic analog clock. A line extended from the North Star to the Pointers becomes the hour hand that sweeps out a circle in the northern sky every 24 hours. A normal analog clock displays 12 hours with the noon/midnight hour at top and 6 p.m./a.m. at the bottom. Our sky clock operates on 24-hour time so its clock face has 24 hours with the 24/0 hour at the top of the "dial" and the 12-hour spot at the bottom. As the Earth turns, the clock's hour hand runs backwards (counterclockwise) at the rate of 15° per hour.

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

Like a broken watch that tells the correct time twice a day, the Dipper clock gives the correct time on March 6th. On that date, if the Polaris-Pointers hour hand points to 22, it’s 10 p.m. If 19, it’s 7 p.m. For all other dates, use this simple equation:

Time = Dipper Time – (2 x number of months since March 6th)

For example, if you face north on the night of April 25th and notice that the celestial hour hand points to 24:00 on the clock, the approximate time will be:

Time = 24 – (2 x 1.6 months) = 24 – 3.2, which is 20.8 hours on the 24-hour clock

Convert the decimal to minutes (0.8 x 60) to get 8:48 p.m. local standard time (LST).

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

When daylight-saving time is in effect remember to add an hour to the Dipper time. When we do this, our crude clock reads 9:48 p.m. local daylight time (LDT). The actual time (based on computer simulation) is 10 p.m., so that's pretty close.

In our calculation, the solution was a positive number. If your answer is negative, subtract it from midnight (24) for the correct time. Based on my own experience with the Dipper clock I've found it accurate to within about 30 minutes. Keep in mind that your time may vary somewhat depending on your location in your time zone — our celestial clock will be a little behind true time if you live toward the western end of the time zone and a little ahead if you’re in the east.

Throughout human history, increasing precision in timekeeping has pushed the advancement of both technology and science. Still, it's fun to look back and take pleasure in knowing that the celestial gears continue to hum along.

CERES MEETS M100

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

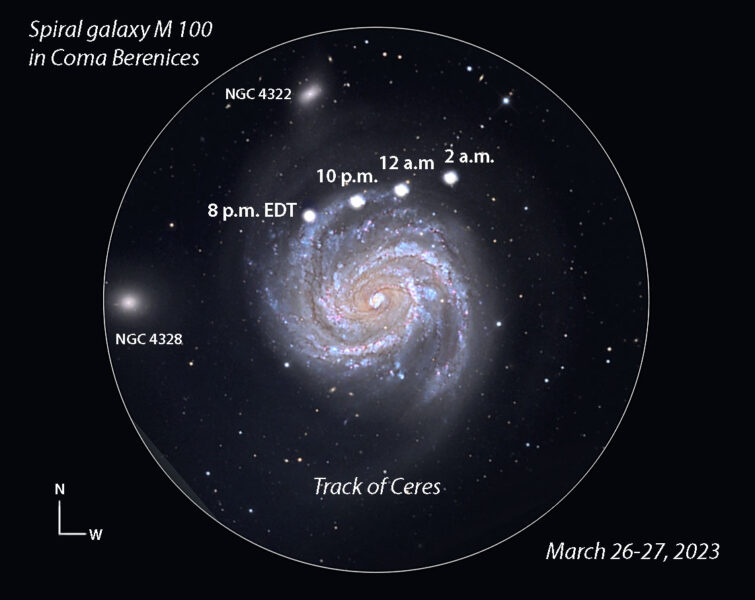

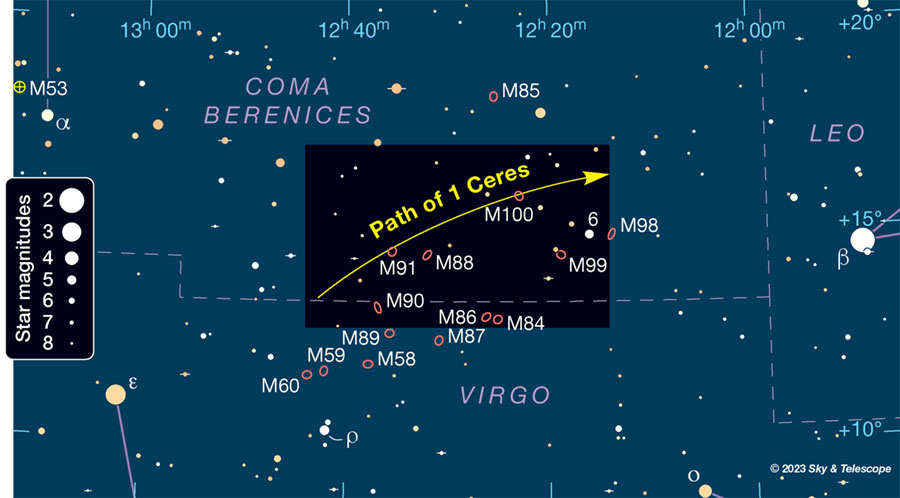

Ceres, the largest asteroid and one of five dwarf planets, reaches opposition on March 21st at magnitude 6.9. Any pair of binoculars will show it as a "star" moving slowly westward across Coma Berenices not far from Leo's Tail. This region of the sky is well known for its plethora of galaxies sought after by amateurs when the snow finally melts away and spring returns. By good fortune Ceres will pass directly in front of the bright 9th-magnitude spiral galaxy M100 on the night of March 26–27. For a few hours it will mimic a brilliant telescopic supernova beaming from one of the galaxy's arms.

How fun to think that despite their apparent proximity Ceres shines from the piddling distance of 240 million kilometers compared to the galaxy's 56 million light-years. For a brief time their light will be co-mingled in breathtaking fashion. A 4-inch telescope will easily show the galaxy as a fuzzy patch with a brighter core, but to see the spiral arms you'll need at least an 8-inch instrument.

If you get skunked by bad weather, Italian astronomer Gianluca Masi plans to livestream the transit starting on March 26th at 11 p.m. EDT (3:00 UT, March 27th) on his Virtual Telescope site. Hopefully, we'll all get to relish one of the sky's finest illusions — effortlessly compressing three dimensions into two. Good luck!

Comments

Post a Comment