It is a fact that even many die-hard Abba fans do not know. Despite selling millions of copies over more than four decades, their massive 1979 hit, Chiquitita, doesn't earn the Swedish supergroup a penny.

"We gave the copyright to Unicef," its composer and founding member of Abba, Bjorn Ulvaeus, told the BBC.

"A lot of money has come in over the years because Chiquitita has been played and streamed a lot, and lots of records have been sold. So, I'm very happy about that."

Written for Unicef's Year of the Child, Chiquitita - which means "Little Girl" in Spanish - was also the first song Abba recorded in Spanish, becoming a huge success across Latin America. From the start, Bjorn Ulvaeus says the band was clear about what they wanted the royalties to be used for.

"I think that the most urgent thing that can be done on this globe is the empowerment of young women and girls. That would change our world," he said. "It's so sad that there are cultures and religions around the globe that just don't give girls equal chances. So, early on we said to Unicef, that's where we want our money to go."

In an echoey hall in the town of La Tinta in Alta Verapaz, the poorest region of Guatemala, a group of indigenous girls perform their own version of Chiquitita, translated into their native Mayan language, Q'eqchi'.

The primary-school-aged children attend health and self-esteem workshops at the Association of Friends of Development and Peace (ADP), one of the oldest NGOs in Guatemala, paid for using the funds from Abba's song.

There is a chronic lack of sexual health education in the Central American nation, especially in impoverished indigenous communities: last year, 346 girls aged 14 and under had babies in Alta Verapaz. Many more under 16 also had children.

One of them was Emma, though that is not her real name.

As she cradles her six-month-old baby boy, Emma practices breathing exercises with one of the ADP's psychologists. A victim of domestic abuse and rape, she has received support on violence prevention and bodily autonomy from the ADP as well as help with breast-feeding.

Speaking to me in Q'eqchi via a translator, Emma tells me the family therapy, which she received alongside her parents, and the one-to-one emotional support has helped her cope with such a violent, forced start to motherhood.

"I've learnt a lot about emotional control," she explained. "I feel stronger and surer of myself. And I'm learning how to look after my baby," she said, the boy's face covered under his mother's shawl.

Emma's story is common in Alta Verapaz. So common, in fact, that her younger sister is also a teenage mother from sexual abuse.

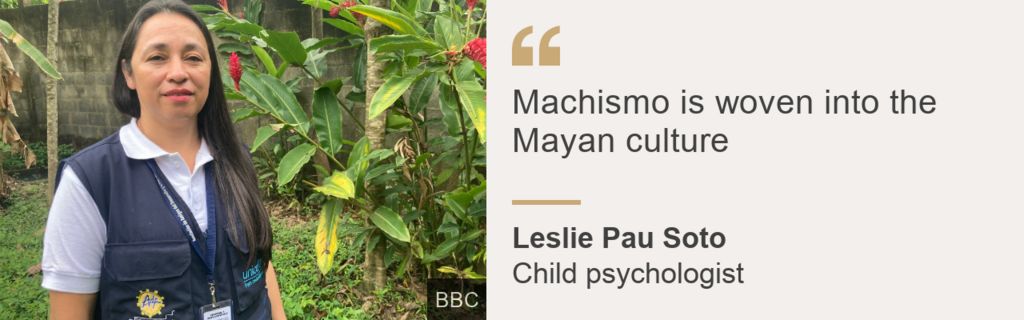

"Machismo is woven into the Mayan culture", said Leslie Pau Soto, one of the ADP's child psychologists.

"Here they produce cardamom, coffee, cacao, maize and beans, and men's physical strength is greatly valued while women are minimised and restricted to the home."

Women are generally not allowed to study, said Ms Pau Soto, and those women who attempt to study or work are stigmatised. Women are "always controlled, obeying whatever the men want", she added, until the men achieve complete dominion over them.

The administration of Guatemala's President, Alejandro Giammattei, has been accused by its critics of failing the victims of domestic violence and rape. Impunity is rife: only one or two cases in every hundred results in the perpetrator being successfully prosecuted or sentenced.

In Alta Verapaz, the state has appointed just one victims' support psychologist for a population of several hundred thousand people. Her name is Annie Juárez.

"We have constant deficiencies," she said, speaking in her dingy office in La Tinta. She insisted they were doing what they could on limited resources, and described a government online portal for victims to denounce abuse.

However, in Guatemala's mountainous regions, there is often no internet coverage and many families are not computer literate.

So the ADP has produced public information spots in Q'eqchi' and other Mayan languages for local radio. They also send out teams of social workers into the more remote communities to offer support to abused children and their families.

In the community of Salac Uno, they have been working with Marta, again not her real name, an eight-year-old girl who was sexually abused by an older boy.

Some families reject the organisation's approach, particularly when the aggressor lives inside the home. However, Marta's mother - Doña Lidia - is a teacher and welcomed the support after the girl's school identified the abuse.

"The men have treated us so badly. But things are changing," she said. "They have to respect us. We know we also have rights."

In the 43 years since its release, Chiquitita's royalties have been used to address some of the most complex issues affecting Central America - from extreme poverty and a generational culture of machismo to domestic violence and rape. Even alcohol abuse among marginalised, indigenous communities.

It's also benefitted countless "chiquititas", like Marta and Emma, along the way with meaningful support in their native language. Before travelling to Guatemala, I asked Bjorn Ulvaeus if he had expected the song to have such an enduring legacy when he wrote it.

"You don't think about the longevity!" he laughed. "You think 'Well, I hope it'll be a hit and it'll be played a lot!'

"Never in my wildest dreams could I have expected it would be so long-lasting and bring in so much money. It's the best legacy anyone could wish for."

Comments

Post a Comment