By Esme Stallard,

BBC News Climate and Science,

A fifth effort to pass a global agreement to protect the world's oceans and marine life has failed.

Talks to pass the UN High Seas Treaty had been ongoing for two weeks in New York, but governments could not agree on the terms.

Despite international waters representing nearly two-thirds of the world's oceans, only 1.2% is protected.

Environmental campaigners have called it a "missed opportunity".

The last international agreement on ocean protection was signed 40 years ago in 1982 - the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

That agreement established an area called the high seas - international waters where all countries have a right to fish, ship and do research.

Marine life living outside of the 1.2% of protected areas are at risk of exploitation from the increasing threats of climate change, overfishing and shipping traffic.

Over the last two weeks 168 members of the original treaty, including the EU, came together to try and make a new agreement.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that documents the status of the world's biodiversity spoke to BBC News during the conference.

Their Senior High Seas Advisor, Kristina Gjerde, explained why this treaty was so important: "The high seas are the vital blue heart of the planet.

"What happens on the high seas affects our coastal communities, affects our fisheries, affects our biodiversity - things we all care so much about."

The negotiations focused on four key areas:

- Establishing marine protected areas

- Improving environmental impact assessments

- Providing finance and capacity building to developing countries

- Sharing of marine genetic resources - biological material from plants and animals in the ocean that can have benefits for society, such as pharmaceuticals, industrial processes and food

More than 70 countries - including the UK - prior to the meeting had already agreed to put 30% of the world's oceans into protected areas.

This would put limits on how much fishing can take place, the routes of shipping lanes and exploration activities like deep sea mining.

Deep-sea mining is when minerals are taken from the sea bed that is 200m or more below the surface. These minerals include cobalt which is used for electronics, but the process could also be toxic for marine life, according to the IUCN.

As of March 2022, the International Seabed Authority, which regulates these activities, had issued 31 contracts to explore the deep sea for minerals.

But countries failed to reach agreement on key issues of fishing rights and also funding and support for developing countries.

World Wildlife Foundation's (WWF) Senior Ocean Governance Expert Jessica Battle - who was at the negotiations - told BBC News that the Arctic was a divisive issue: "As it opens up due to climate change and we have much shorter winters, that is going to open up a whole new area of extraction."

There are concerns that without this treaty not only will marine species not be protected but also some species will never be discovered before they become extinct.

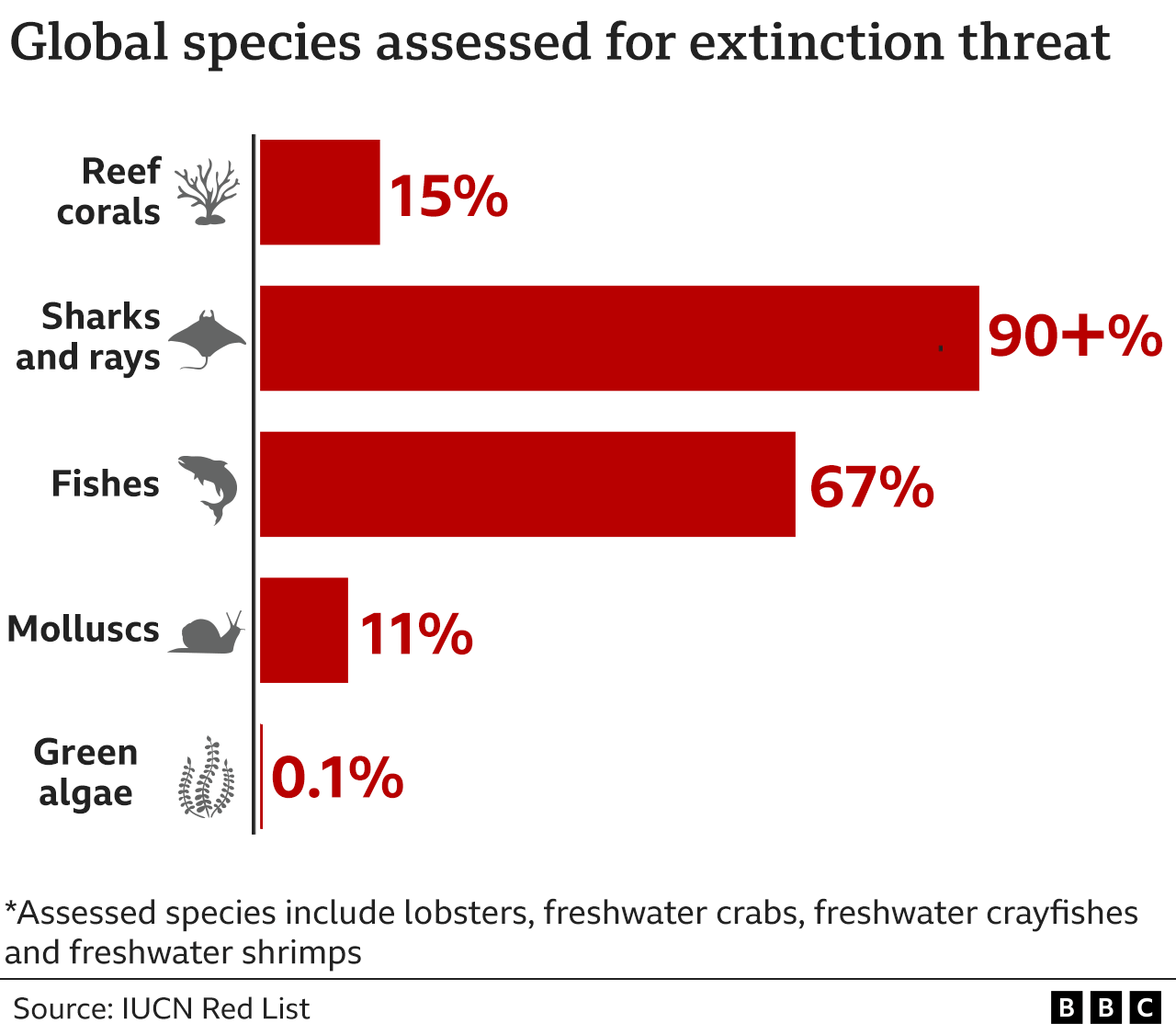

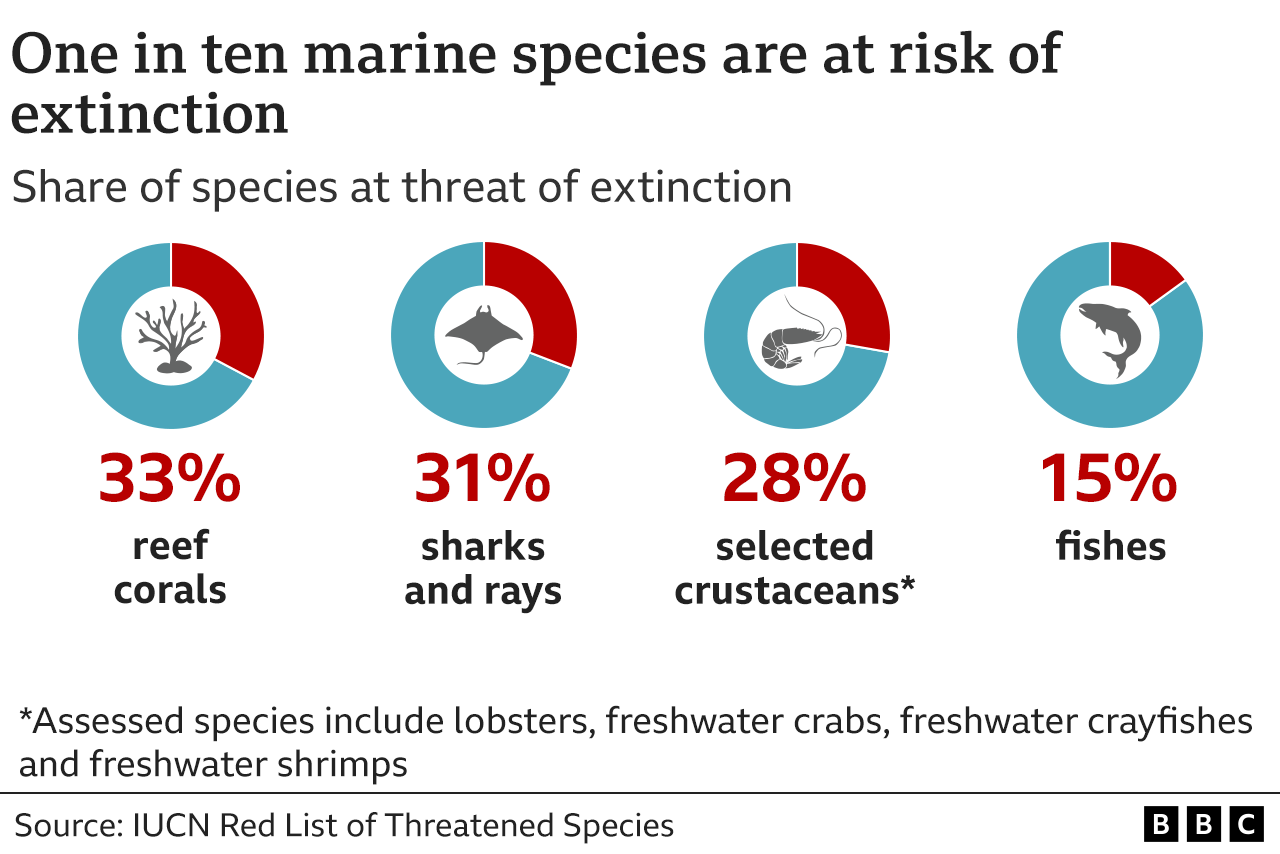

Research published earlier this year, and funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, suggests that between 10% and 15% of marine species are already at risk of extinction.

Sharks and rays are among the species set to lose out from the failure to pass the treaty.

According to the IUCN they are facing a global extinction crisis - and are one of the most threatened species groups in the world.

Sharks and other migratory species such as turtles and whales move through the world's oceans interacting with human activities like shipping which can cause them severe injuries and death.

All species of sharks and rays are also overfished - leading to rapid population decline.

Such reduction in animal numbers have been observed across most major marine groups.

It is not yet clear when countries will come back together to continue negotiations - but a deadline has been set for the end of the year.

They have a jam-packed calendar of international meetings on other matters between now and January - including the annual climate conference COP27 and the UN General Assembly meeting.

If the treaty does get signed there will still be further work to do.

The treaty will not outline what areas of the ocean will be placed under marine protection - just the process by which organisations and countries can apply for it.

Equally the treaty is not expected to include exact figures on what financial support developing nations will receive from developed countries, Liz Karan Project Director for the Pews High Seas Campaign told BBC News.

And Ms Karan said in the previous treaty from 1982 there were promises for support that were not fulfilled, and this has left some developing nations frustrated.

The fate of the oceans also depends on global action on climate change - which is decided as part of other UN negotiations.

The world's seas have absorbed 90% of the warming that has occurred due to increasing greenhouse gases produced by human activities, according to Nasa.

"The half of our planet which is high seas is protecting terrestrial life from the worst impacts of climate change," said Prof Alex Rogers from Oxford University, UK, who has provided evidence to inform the UN treaty process.

Comments

Post a Comment