From :- Sky & Telescope

By :- Bob King

Editted by : - Amal Udawatta

Eliot Herman

Aristotle postulated that meteors occurred when dry and smoky exhalations rose from cracks in the ground and ascended into the sublunar realm, where they suddenly burst into flame. The reality is much more exciting. Sand-sized grains spalled from 4.5-billion-year-old interplanetary travelers strike Earth's atmosphere at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, fast enough to heat them to incandescence and etch the heavens with fleeting streaks of glowing air.

Sky & Telescope

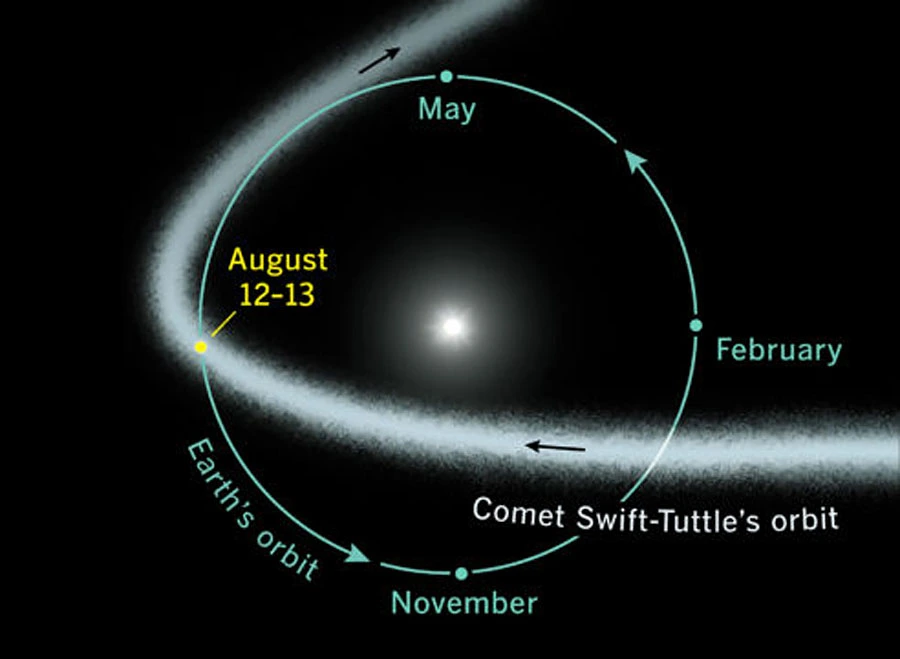

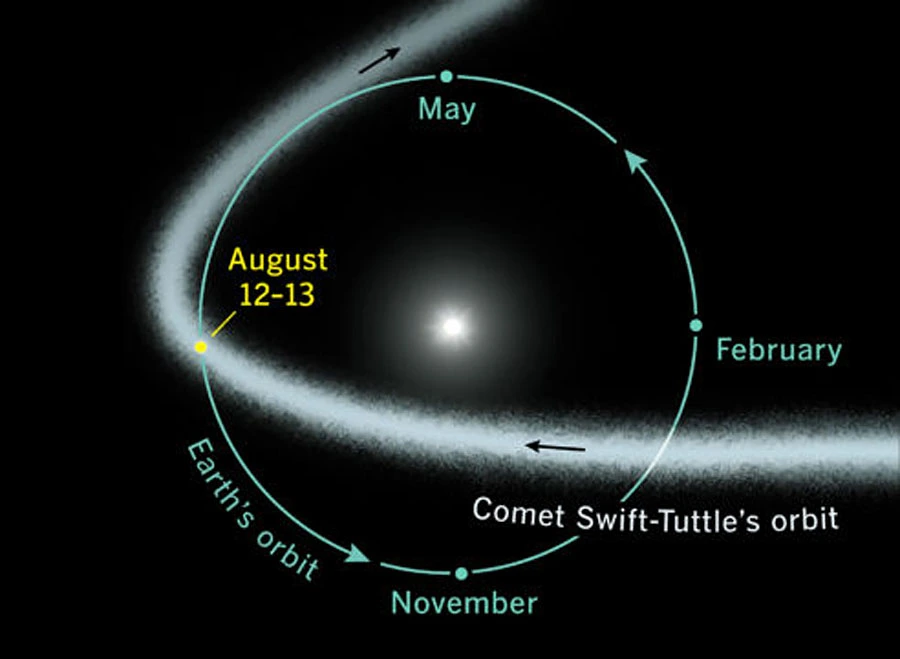

Meteors zip by day and night, but a few times a year they arrive in bunches called meteor showers. Each shower has a source. For the Perseids, it's comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. Every 133 years, when it ventures into the inner solar system, the Sun vaporizes a fraction of the comet's icy nucleus, which is rich in dust and small rock fragments. These spread out along its path to create a ribbon of debris. Every year from mid-July to late August, Earth crosses the comet's orbit and slams into the particles at some 60 kilometers per second (134,000 mph), so fast they incandesce (become luminous) as meteors.

The comet's trail is broad with a denser core, so we see a smattering of meteors well before maximum, a significant uptick when we plow through the center, and then a decline as Earth speeds away from the swarm. Meteor rates reach a maximum during core passage, which will happen starting Tuesday night, August 12-13.

Staying positive

Under a truly dark, moonless sky, we might spot 50 to 80 Perseids an hour during the shower's peak. But this year, the waning gibbous Moon will likely reduce that number by half, or more. The Moon rises around 9:30-10 p.m. local time (the same time the sky is getting dark), and it shines the entire night. While unfortunate, the Moon's presence isn't a deal-breaker.

Stellarium with annotations by Bob King

Keep in mind that fainter meteors, the ones that moonlight will erase, typically outnumber brighter ones. Since the Perseids produce more fireballs — meteors as bright as, or brighter than, Venus — than any other major shower, their number will be unaffected. You could say that we'll only see the cream of the crop this time around.

To further improve prospects of seeing more meteors, keep the Moon at your back so it doesn't accidentally dazzle your eyes. As with all meteor showers, it's not necessary to stare at the streaming point, called the radiant. Perseids flash in any and every corner of the sky. What unites them is that they all point back to their origin in northwestern Perseus below the W of Cassiopeia.

Bob King

Between dusk and moonrise, when Perseus hovers low in the northeastern sky, be on the lookout for earthgrazers — meteors that strike the atmosphere at a very shallow angle and skim along its edge like a rock skipped across water. They flare for multiple seconds as if unquenchable and leave behind long, bright trails. Robert Lunsford, Secretary General of the International Meteor Organization, notes that earthgrazers often appear just above the eastern and western horizons. An unobstructed view in either or both directions will be the best way to catch one. Lunsford also has noticed that "the colors of bright Perseid meteors in bright moonlight seem to be enhanced." During one moonlit Perseid night, he recorded his only pink and purple meteors.

Bob King

Let nature Drive

A lounge chair is all you'll need to watch and enjoy the Perseids. Sit back and relax with a blanket or sleeping bag with zero expectations, and let the rhythm of the shower carry you off into a cosmic reverie. If you're new to the night sky, download a stargazing app like Stellarium Mobile or Star Walk 2 and add a constellation or two to your life list while waiting for those flashy fireballs to show. Sharing the shower with family or friends makes for a peaceful evening of quiet conversation punctuated by the occasional "Wow!" when a bright meteor splits the sky.

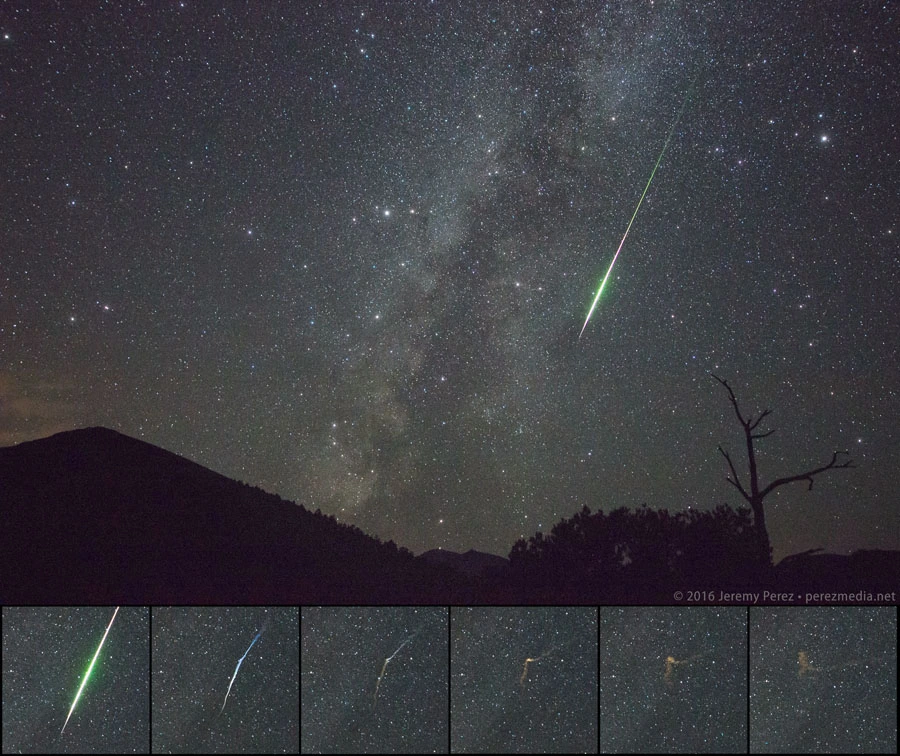

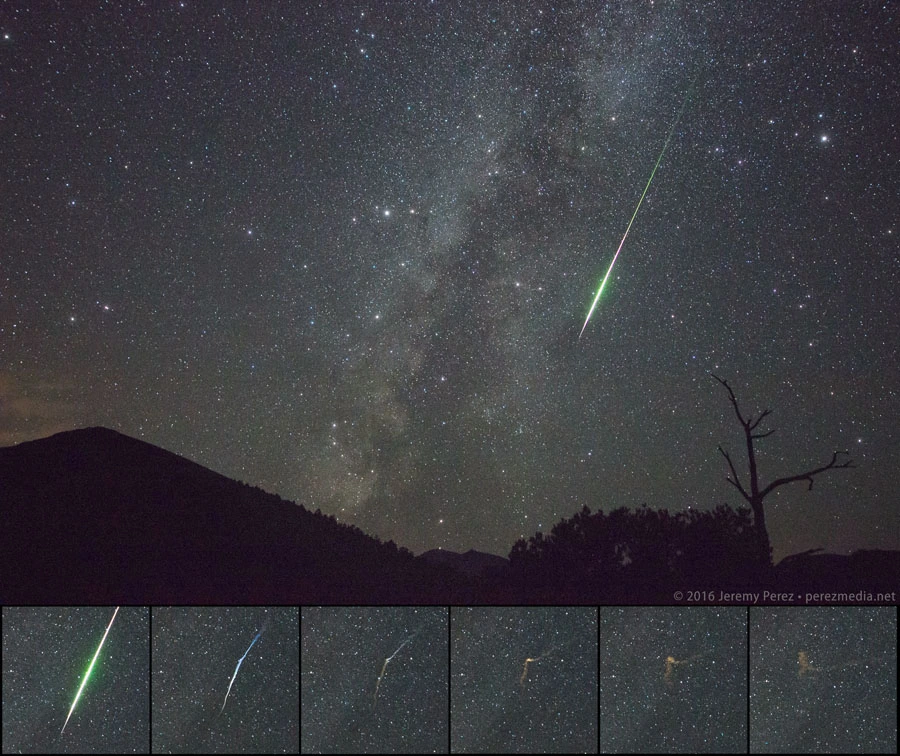

Jeremy Perez

Moonlight is your friend

Have a digital camera and tripod? You can still photograph meteors if you're careful not to overexpose. Moonlight has its advantages. Instead of dark silhouettes framing the foreground of your meteor scenes, the light provides a welcome source of illumination, highlighting the color and texture of a rugged mountain cliff, hay field or waterfall. Since the Moon shines by reflected sunlight, your time-exposures will show a blue sky instead of gray or some off-color hue from local light-pollution.

I like to use a moderately wide-angle lens — at least a 35-mm — with the iris wide open to allow in the maximum amount of light. You can autofocus on the Moon. Then click the lens back to M (manual mode), and your focus will be set for the night. Experiment with a starter ISO of 800 and exposures between 15 and 30 seconds. Check the camera LCD backscreen replay and adjust the exposure time/ISO speed as necessary. A remote shutter release or intervalometer (built into certain camera models) will free you from constantly having to push the shutter button. You can easily purchase one online.

Sure, the Moon will be a problem. But clouds are worse. Don’t miss one of the best meteor showers of the year.

Eliot Herman

Aristotle postulated that meteors occurred when dry and smoky exhalations rose from cracks in the ground and ascended into the sublunar realm, where they suddenly burst into flame. The reality is much more exciting. Sand-sized grains spalled from 4.5-billion-year-old interplanetary travelers strike Earth's atmosphere at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, fast enough to heat them to incandescence and etch the heavens with fleeting streaks of glowing air.

Sky & Telescope

Meteors zip by day and night, but a few times a year they arrive in bunches called meteor showers. Each shower has a source. For the Perseids, it's comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. Every 133 years, when it ventures into the inner solar system, the Sun vaporizes a fraction of the comet's icy nucleus, which is rich in dust and small rock fragments. These spread out along its path to create a ribbon of debris. Every year from mid-July to late August, Earth crosses the comet's orbit and slams into the particles at some 60 kilometers per second (134,000 mph), so fast they incandesce (become luminous) as meteors.

The comet's trail is broad with a denser core, so we see a smattering of meteors well before maximum, a significant uptick when we plow through the center, and then a decline as Earth speeds away from the swarm. Meteor rates reach a maximum during core passage, which will happen starting Tuesday night, August 12-13.

Staying positive

Under a truly dark, moonless sky, we might spot 50 to 80 Perseids an hour during the shower's peak. But this year, the waning gibbous Moon will likely reduce that number by half, or more. The Moon rises around 9:30-10 p.m. local time (the same time the sky is getting dark), and it shines the entire night. While unfortunate, the Moon's presence isn't a deal-breaker.

Stellarium with annotations by Bob King

Keep in mind that fainter meteors, the ones that moonlight will erase, typically outnumber brighter ones. Since the Perseids produce more fireballs — meteors as bright as, or brighter than, Venus — than any other major shower, their number will be unaffected. You could say that we'll only see the cream of the crop this time around.

To further improve prospects of seeing more meteors, keep the Moon at your back so it doesn't accidentally dazzle your eyes. As with all meteor showers, it's not necessary to stare at the streaming point, called the radiant. Perseids flash in any and every corner of the sky. What unites them is that they all point back to their origin in northwestern Perseus below the W of Cassiopeia.

Bob King

Between dusk and moonrise, when Perseus hovers low in the northeastern sky, be on the lookout for earthgrazers — meteors that strike the atmosphere at a very shallow angle and skim along its edge like a rock skipped across water. They flare for multiple seconds as if unquenchable and leave behind long, bright trails. Robert Lunsford, Secretary General of the International Meteor Organization, notes that earthgrazers often appear just above the eastern and western horizons. An unobstructed view in either or both directions will be the best way to catch one. Lunsford also has noticed that "the colors of bright Perseid meteors in bright moonlight seem to be enhanced." During one moonlit Perseid night, he recorded his only pink and purple meteors.

Bob King

Let nature Drive

A lounge chair is all you'll need to watch and enjoy the Perseids. Sit back and relax with a blanket or sleeping bag with zero expectations, and let the rhythm of the shower carry you off into a cosmic reverie. If you're new to the night sky, download a stargazing app like Stellarium Mobile or Star Walk 2 and add a constellation or two to your life list while waiting for those flashy fireballs to show. Sharing the shower with family or friends makes for a peaceful evening of quiet conversation punctuated by the occasional "Wow!" when a bright meteor splits the sky.

Jeremy Perez

Moonlight is your friend

Have a digital camera and tripod? You can still photograph meteors if you're careful not to overexpose. Moonlight has its advantages. Instead of dark silhouettes framing the foreground of your meteor scenes, the light provides a welcome source of illumination, highlighting the color and texture of a rugged mountain cliff, hay field or waterfall. Since the Moon shines by reflected sunlight, your time-exposures will show a blue sky instead of gray or some off-color hue from local light-pollution.

I like to use a moderately wide-angle lens — at least a 35-mm — with the iris wide open to allow in the maximum amount of light. You can autofocus on the Moon. Then click the lens back to M (manual mode), and your focus will be set for the night. Experiment with a starter ISO of 800 and exposures between 15 and 30 seconds. Check the camera LCD backscreen replay and adjust the exposure time/ISO speed as necessary. A remote shutter release or intervalometer (built into certain camera models) will free you from constantly having to push the shutter button. You can easily purchase one online.

Perseid persistence

Our ancestors have been watching the Perseids for centuries. The earliest records go back to China in 36 A.D. when "more than 100 meteors flew thither in the morning.” Although numerous mentions were made of the shower thereafter, it wasn't until 1836 that its annual appearance was finally recognized by Belgian French astronomer Adolphe Quételet, who also gave the shower its name. In 1865, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, of the Martian canals fame, noted the similarity of the orbit of 109P/Swift-Tuttle with the Perseids and proposed it as the source of the shower.

Stellarium with annotations by Bob King

On a final note, there's an added incentive if you get up before dawn to take in the show. In a wonderful coincidence, Jupiter and Venus will be choreographing a close conjunction right around the shower's peak. On the morning of August 12, they'll be closest at just 0.9° apart. Their separation expands to 1.4° the following morning. If there's a better way to wrap up a night of meteor-watching, I can't think of one. Good luck, and clear skies!

Comments

Post a Comment