While looking at the Earth-lit portion of the 2.6-day-old Moon through 10×50 binoculars on April 29th, I could see more than a half-dozen lunar maria along with the prominent rayed craters Copernicus and Kepler. Another bright patch caught my eye southeast of Mare Nubium that I took to be Tycho, one of the Moon's most prominent craters. But looking closer, CassiniI realized that wasn't the case. That luminous smear was in fact Cassini's Bright Spot. Named for the 17th-century Italian-born French astronomer Giovanni Cassini, it's been dazzling observers for centuries.

Copyright: Observatoire de Paris, First Print, Inv. I 1576

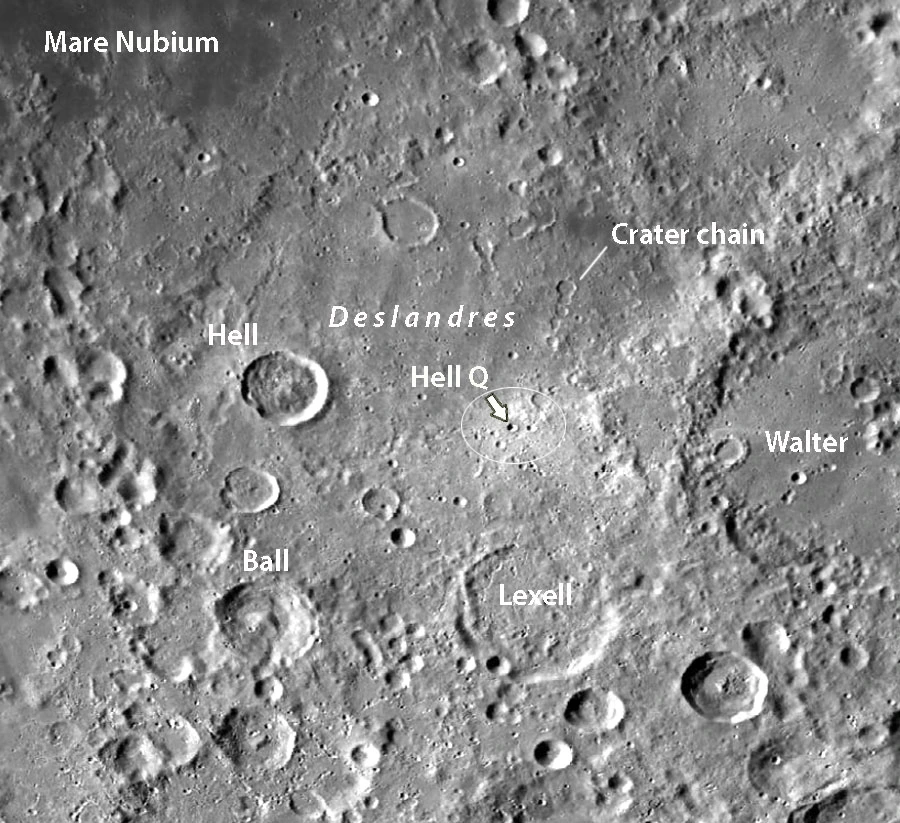

Cassini apparently mistook what we now call crater Hell Q and its tiny system of brilliant rays as a "white cloud" during his observations in 1671. Sometime later, the great observer noted that the cloud had "dissipated" to reveal a newly formed crater in its place. More likely, telescopic limitations at the time contributed to the misperception.

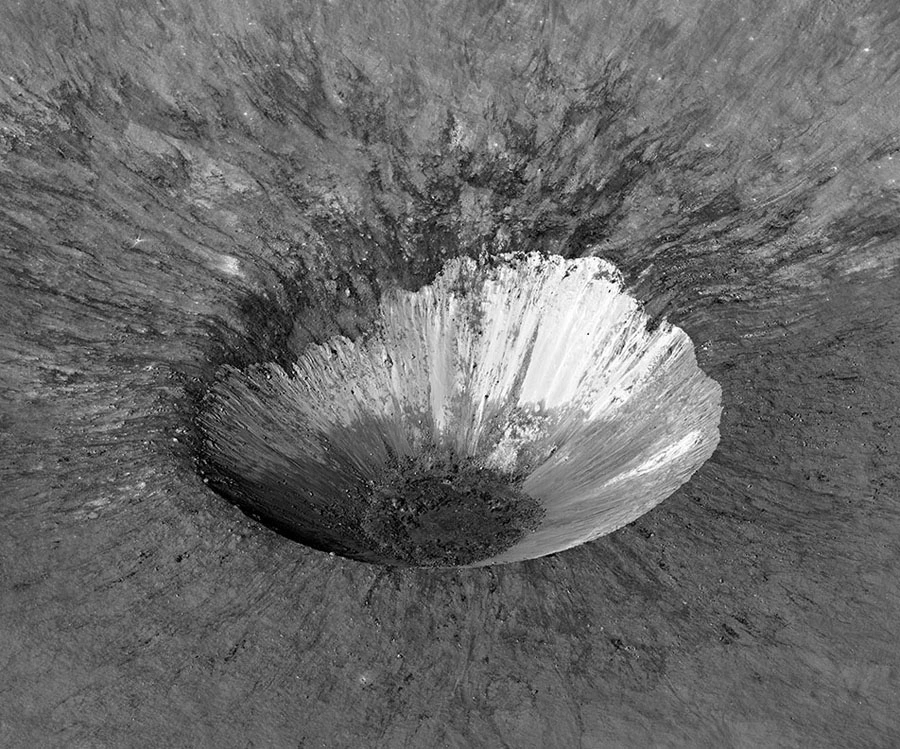

In his book The Modern Moon: A Personal View, Sky & Telescope Contributing Editor Charles Wood describes Cassini's Bright Spot as a "3-km-wide fresh crater with spikes of rays extending out a few tens of kilometers." Craters like Tycho and Hell Q reveal their relative youth by their bright interiors and the brilliance of their ray systems.

Bob King

Asteroid impacts excavate rock and dust from beneath the lunar surface that haven't been exposed to sunlight for eons. Because the material is relatively unaffected by the constant bombardment of solar particles and cosmic rays, which darkens lunar surface soils over time, it exhibits a much lighter tone. In addition, rocks ejected from the primary impact form secondary craters that further expose long-buried crustal rocks.

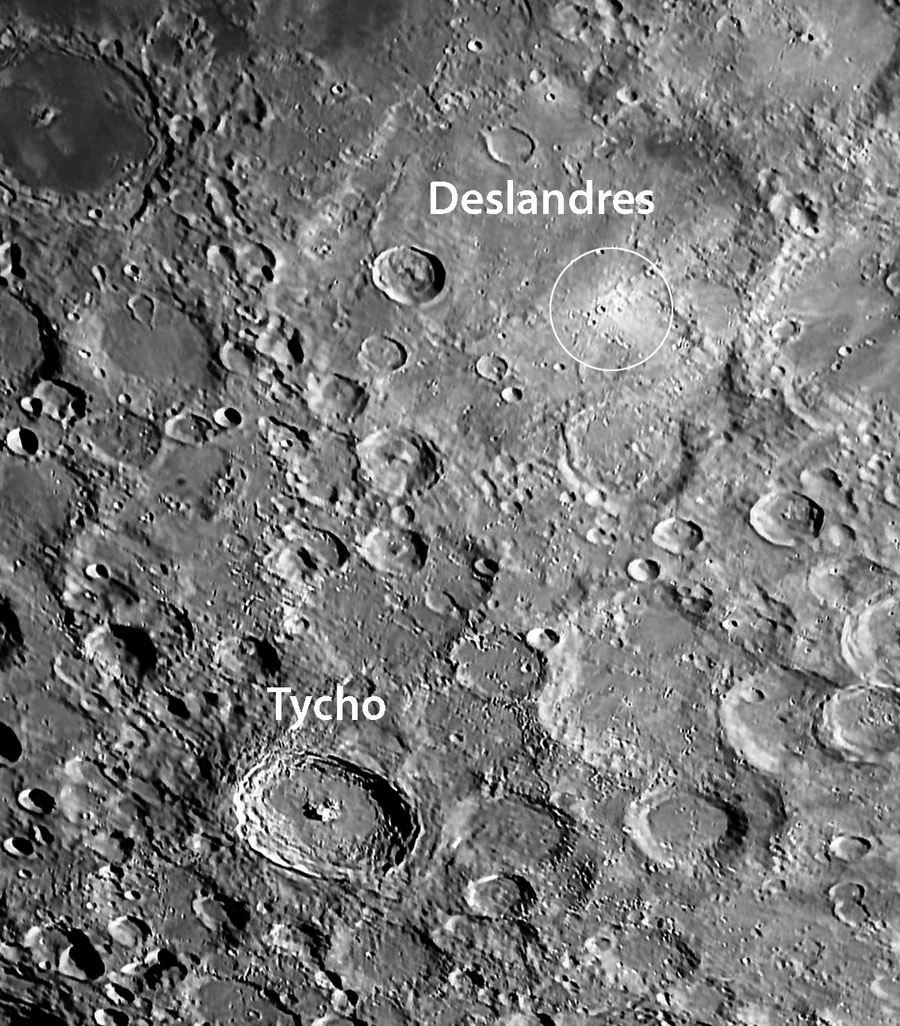

Tycho is one of the youngest lunar craters, with an estimated age of 108 million years. It formed during Earth's Late Cretaceous epoch, when dinosaurs were king. Astronomers estimate the impactor's diameter to be between 6 and 10 km, which coincidentally was about the size of the asteroid that led to the extinction of the giant reptiles some 42 million years later.

Although the age of Hell Q isn't known precisely, its sharp outline and rays are good indicators of its youth. One thing's for certain — the area reflects light so well it gives Aristarchus, the Moon's brightest large feature, a run for its money. The night I observed the spot in earthshine, Hell Q was easier to see than Aristarchus. Granted, that was due in part to favorable viewing circumstances at the time: libration in longitude had rotated Aristarchus away from our line of sight toward the Moon's western limb; the Hell Q region was more centrally located.

NASA

Sunlight first touches Cassini's Bright Spot when the Moon is about 8.5 days old, and the spot remains in view for about two weeks. Even in poor seeing on May 5th, when the Moon's age was 8.8 days, I discerned the crater Hell Q — 3.4 kilometers (2.1 miles) across — and Cassini's Bright Spot in my 10-inch reflector at 171×. The next night, the crater was a bit more difficult to see, but the spot was considerably brighter. Both are located within the large, beaten-down confines of Deslandres. With a diameter of 227 km, Deslandres is the third largest crater on the lunar nearside after Clavius (231 km) and Bailly (303 km).

Robert Reeves

NASA / LRO

Even among Tycho's spatter of rays, Hell Q and its environs stand out as a radiant blob that shines even brighter than the famous crater at full Moon. Although I've yet to try, it might be possible to see Cassini's Bright Spot as an enhancement within Tycho's rays without optical aid especially during favorable librations, when the Moon's Southern Hemisphere tilts into good view.

As a side note, Hell Q is named after 18th-century Hungarian astronomer and Jesuit priest Maximilian Hell. His original surname was Höll, which he later changed to Hell. Hell's native tongue was German. In that language, "hell" means "bright." How fitting!

Comments

Post a Comment